Alternatives

The media gives us a very simple story about what preceded the Ukraine war.

I’ll use this piece to talk about whether it was necessary to integrate Ukraine into NATO. Someone might read my 12 February 2023 piece—which talks about the history that preceded the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine—and say “Maybe integrating Ukraine into NATO was indeed ‘highly provocative’, but how else could we have protected Ukraine from Russian aggression?”. This piece will address that question—I’ll quote from various commentaries and then give my own thoughts.

Clarification

I assume that everyone reading this piece knows that (1) Putin is a murderous thug, (2) Russia is a kleptocracy, and (3) Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine was an enormous war crime. These points are completely obvious and uncontroversial—that’s why it’s demeaning to have to say them over and over.

There is—disturbingly—a fundamental conflation of what it means to understand and what it means to condone. To understand the Kremlin is not to condone Russian atrocities. The Kremlin has security concerns—understanding these doesn’t mean supporting Russian crimes. To understand the Russian support for Putin is not to say that Putin is a moral—or effective—leader. A 2017 article says that “results suggest that the main obstacle at present to the emergence of a widespread opposition movement to Putin is not that Russians are afraid to voice their disapproval of Putin, but that Putin is in fact quite popular”—how can we help democratize Russia if we don’t understand the basis of Putin’s popular support? We want to understand the Russian people and their leaders—understanding is a good thing that helps us improve the world.

Matlock’s Commentary

Jack F. Matlock Jr. writes in a 5 November 2022 commentary: “it is not Russian interference that created Ukrainian disunity but rather the haphazard way the country was assembled from parts that were not always mutually compatible”; the “territory of the Ukrainian state claimed by the government in Kyiv was assembled, not by Ukrainians themselves but by outsiders, and took its present form following the end of World War II”; to “think of it as a traditional or primordial whole is absurd”; and this “applies a fortiori to the two most recent additions to Ukraine—that of some eastern portions of interwar Poland and Czechoslovakia, annexed by Stalin at the end of the war, and the largely Russian-speaking Crimea, which was transferred from the Russian Socialist Federated Soviet Republic (RSFSR) well after the war”.

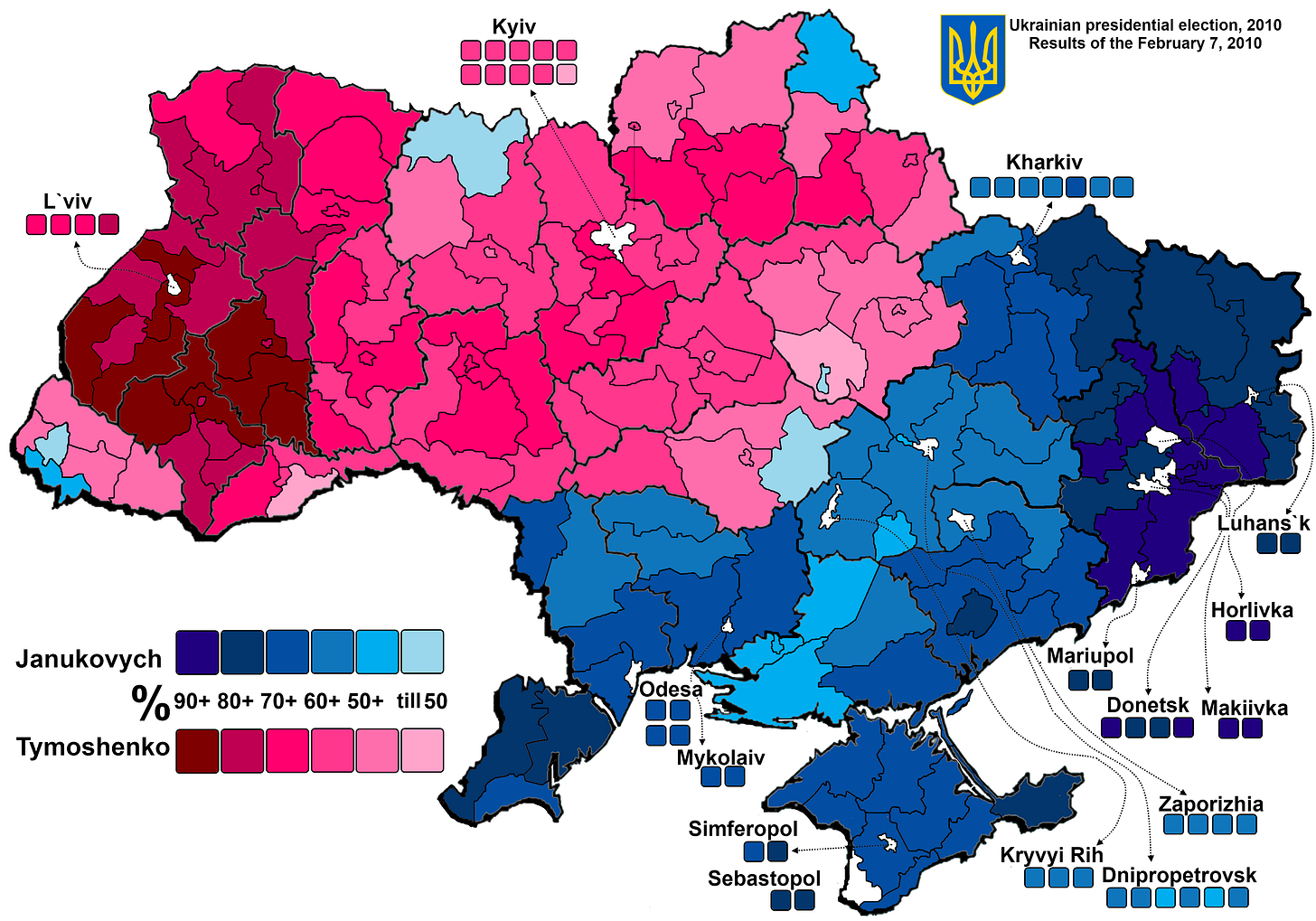

The “lumping together of people with strikingly different historical experience and comfortable in different (though closely related) languages, underlies the current divisions”; if “one takes Galicia and adjoining provinces in the west on the one hand and the Donbas and Crimea in the east and south on the other as exemplars of the extremes, the areas in between are mixed, proportions gradually shifting from one tradition to the other”; there “is no clear dividing line, and Kyiv/Kiev would be claimed by both” traditions; from “its inception as an internationally recognized independent state, Ukraine has been deeply divided along linguistic and cultural lines”; Ukraine has nevertheless “maintained a unitary central government rather than a federal one that would permit a degree of local autonomy”; the “constitution gave the elected president the power to appoint the chief executives in the provinces (oblasti) rather than having them subject to election in each province—as is the case, for example—in the United States”; and the “map of election results in 2010” shows “how closely the political divide in Ukraine parallels the linguistic divide”.

I’ll include two maps—an ethnolinguistic one and then one showing the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election results—from Wikimedia Commons. A user named Yerevanci created the first and a user named Vasyl` Babych created the second:

I recommend the 9 December 2013 WaPo piece “This one map helps explain Ukraine’s protests”—that piece includes the first map above.

Matlock says: the “Ukrainian revolution of 2014 started with protests over President Yanukovich’s decision not to sign an agreement with the European Union”; the “United States and the EU openly supported the demonstrators and spoke of detaching Ukraine from what one might call the Russian (past Soviet) security sphere and attaching it to the West through EU and NATO membership”; never “mind that Ukraine was unable at that time to meet the normal requirements for either EU or NATO membership”; violence “started, first in the Ukrainian nationalist West, with irregular militias taking over the local offices headed by Yanukovich appointees”; on “February 20, 2014, demonstrations in Kyiv, which up to then had been largely peaceful, turned violent even though a compromise agreement had been reached to hold early elections”; many “demonstrators were shot by sniper fire and President Yanukovich fled the country”; demonstration “leaders claimed that the government’s security force, the Berkut, was responsible for initiating the shooting”; “subsequent trials failed to substantiate this”; and in “fact, most of the sniper fire came from buildings controlled by the demonstrators”.

The “United States and most Western countries immediately recognized the successor government”; “Russia and many Russian-speaking Ukrainians considered Yanukovich’s ouster the result of an illegal coup d’etat”; a “rebellion occurred in the Eastern provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk and Russia supported the rebels with military equipment and irregular forces”; in “Crimea, local leaders declared independence and requested annexation by Russia”; a “referendum was conducted under the watchful eye of ‘little green men’ infiltrated from Russia”; there “was no resistance by Ukrainian military or police forces”; “Russia officially annexed the peninsula when the referendum resulted in an overwhelming pro-Russian vote”; and there “was no fighting and no casualties in Crimea”.

In “February 2015 an agreement was reached (‘Minsk agreement’) to bring the Donbas back under Kiev’s control by allowing a degree of autonomy, including election of local officials, and amnesty for the secessionists”; unfortunately, “the Ukrainian legislature (Verkhovna Rada) has refused to amend the constitution to provide for a federal system or to proclaim an amnesty for the secessionists”; separate “sets of U.S. and EU economic sanctions against Russia have been declared in respect to the Crimea and the Donbas”; and “most have seemed to stimulate hostile emotions rather than encourage solution of the problems”.

What “needs to be understood is that Russia perceives these issues as matters of vital national security”; “Russia is extremely sensitive about foreign military activity adjacent to its borders, as any other country would be and the United States always has been”; and it “has signaled repeatedly that it will stop at nothing to prevent NATO membership for Ukraine”.

One “persistent U.S. demand is that Ukraine’s territorial integrity be restored”; “the U.S. is party to the Budapest Memorandum in which Russia guaranteed Ukraine’s territorial integrity in return for Ukraine’s transfer of Soviet nuclear weapons to Russia for destruction in accord with U.S.-Soviet arms control agreements”; what “the U.S. demand ignores is that, under traditional international law, agreements remain valid rebus sic stantibus (things remaining the same)”; when “the Budapest memorandum was signed in 1994 there was no plan to expand NATO to the east and Gorbachev had been assured in 1990 that the alliance would not expand”; and when “in fact it did expand right up to Russia’s borders, Russia was confronted with a radically different strategic situation than existed when the Budapest agreement was signed”.

Ukraine “can never be a united, prosperous country unless it has reasonably close and civil relations with Russia”; that means—among other things—“giving its Russian-speaking citizens equal rights to their language and culture”; and the “legal arguments and appeals to abstract concepts are beside the point”.

Mearsheimer’s Commentary

John Mearsheimer writes in his 2014 Foreign Affairs piece “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault”: “the United States and its European allies share most of the responsibility for the crisis”; “Russia’s invasion of Georgia in August 2008 should have dispelled any remaining doubts about Putin’s determination to prevent Georgia and Ukraine from joining NATO”; and “despite this clear warning, NATO never publicly abandoned its goal of bringing Georgia and Ukraine into the alliance”.

Yanukovych—in November 2013—“rejected a major economic deal he had been negotiating with the EU and decided to accept a $15 billion Russian counteroffer instead”; that “decision gave rise to antigovernment demonstrations that escalated over the following three months and that by mid-February had led to the deaths of some one hundred protesters”; on “February 21, the government and the opposition struck a deal that allowed Yanukovych to stay in power until new elections were held”; “it immediately fell apart, and Yanukovych fled to Russia the next day”; the “new government in Kiev was pro-Western and anti-Russian to the core”; “it contained four high-ranking members who could legitimately be labeled neofascists”; “the full extent of U.S. involvement has not yet come to light”; and it’s “clear that Washington backed the coup”.

For “Putin, the time to act against Ukraine and the West had arrived”; shortly “after February 22, he ordered Russian forces to take Crimea from Ukraine”; “soon after that, he incorporated it into Russia”; the “task proved relatively easy, thanks to the thousands of Russian troops already stationed at a naval base in the Crimean port of Sevastopol”; “Crimea also made for an easy target since ethnic Russians compose roughly 60 percent of its population”; and most “of them wanted out of Ukraine”.

Putin next “put massive pressure on the new government in Kiev to discourage it from siding with the West against Moscow”; “he has provided advisers, arms, and diplomatic support to the Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine, who are pushing the country toward civil war”; he “has massed a large army on the Ukrainian border, threatening to invade if the government cracks down on the rebels”; and “he has sharply raised the price of the natural gas Russia sells to Ukraine and demanded payment for past exports”.

Given “that most Western leaders continue to deny that Putin’s behavior might be motivated by legitimate security concerns, it is unsurprising that they have tried to modify it by doubling down on their existing policies and have punished Russia to deter further aggression”; the West is relying “on economic sanctions to coerce Russia into ending its support for the insurrection in eastern Ukraine”; in “July, the United States and the EU put in place their third round of limited sanctions, targeting mainly high-level individuals closely tied to the Russian government and some high-profile banks, energy companies, and defense firms”; they “also threatened to unleash another, tougher round of sanctions, aimed at whole sectors of the Russian economy”; “even if the United States could convince its allies to enact tough measures, Putin would probably not alter his decision-making”; history “shows that countries will absorb enormous amounts of punishment in order to protect their core strategic interests”; and there’s “no reason to think Russia represents an exception to this rule”.

Quigley’s Commentary

John Quigley writes in his 9 May 2022 Responsible Statecraft piece: the “situation of the Russian speaking population in the eastern reaches of Ukraine first drew international attention in 1994”; the “Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe, which shortly thereafter was re-named Organization on Security and Co-operation in Europe, understood that the existence of clusters of Russian speakers in newly independent states on Russia’s periphery was a recipe for conflict”; the “situation was reminiscent of how the stranding of populations of German speakers after the World War I collapse of the German and Austrian empires helped bring about World War II”; the “Conference began quiet efforts in preventive diplomacy, to convince the newly independent states to treat their Russian populations fairly”; “Crimea was a particular focus of the Conference’s attention”; the “Conference asked three of its member states—Germany, Italy, and the United States—each to appoint an ‘expert on constitutional matters’ to ‘facilitate the dialogue between the Central Government and Crimean authorities concerning the autonomous status of the Republic of Crimea within Ukraine’”; and “I was appointed by the U.S. State Department”.

The “dilemma, as I shuttled back and forth between Kyiv and Simferopol, the Crimean capital, was that Crimea fell under Ukrainian sovereignty, but its population was majority Russian and saw no reason to be part of Ukraine”; in “meetings with Crimean authorities, I was confronted with claims for independence based on self-determination”; “I tried to find a way for the Ukrainian government to give enough autonomy that the Crimeans would stop demanding separation”; after “a series of meetings with Ukrainian and Crimean officials, I devised a plan for full-throated autonomy for Crimea, as a treaty that could have been concluded between Ukraine and Crimea”; to “protect Crimea from infringement, I included international oversight to be exercised by the CSCE”; Quigley’s “treaty went nowhere, however”; the “CSCE High Commissioner for Minorities, a seasoned Dutch diplomat named Max van der Stoel, told me that the Ukrainian government would not abide international oversight”; he “may have been correct, but the CSCE was not prepared to pressure the Ukraine government on the matter”; “Ukraine cracked down on the Crimean Republic, and the conflict remained unresolved”; tension “simmered until 2014, by which time Russia was prepared to act to take Crimea back”; and “Crimea was then formally merged into the Russian Federation”.

A “similar ethnic dynamic developed in the Donbas”; there “the sentiment on the part of the Russian speaking population was less for separation from Ukraine than for autonomy”; in “2014, agreement between Russia and Ukraine was brokered by Germany, France, and the United States, whereby Ukraine would formalize autonomy for the Donbas”; “Ukraine President Volodomyr Zelensky came into office saying he would follow through on this pledge”; “if Ukraine does anything even close to implementing the Minsk agreement, Russia could say that the aim of its invasion has been accomplished”; regarding the Donbas, “it would not be difficult for Ukraine to offer more autonomy than it has to date”; the “Russian military assault seems to have pushed many Russian speakers in the Donbas to embrace Ukraine”; they “may be less demanding on autonomy than before”; a “renewed Ukrainian commitment on autonomy could be framed by the Russian government as a victory”; and any “potential deal could be sweetened for Russia if Ukraine were to show flexibility on the status of Crimea”.

Lieven’s Commentary

Anatol Lieven writes in his 15 November 2021 Nation piece “Ukraine: The Most Dangerous Problem in the World”: since “the Ukrainian revolution and the Donbas rebellion of 2014, successive Ukrainian governments have vowed to recover the Donbas—by force if necessary”; despite “a ceasefire in 2015 that suspended full-scale war, probing attacks and retaliations by both sides have led to repeated clashes, as in March and April of this year”; and successive “US administrations have expressed strong support for the Ukrainian side and for future NATO membership (so far blocked by Germany and France)”.

Perhaps “the most tragic aspect of the seemingly unending Donbas dispute is that, while it may be one of the most dangerous crises in the world today, it is also in principle the most easily solved”; a “solution exists that was drawn up by France, Germany, Russia, and Ukraine and endorsed by the US, the European Union, and the United Nations”; this “solution corresponds to democratic practice, international law and tradition, and America’s own past approach to the settlement of ethnic and separatist conflicts”; “it requires no concessions of real substance by either Ukraine or the US”; the “depth of Russia’s commitment to this solution would of course have to be carefully tested in practice”; and “if US administrations, the political establishment, and the mainstream media have quietly buried it, this is because of the refusal of Ukrainian governments to implement the solution and the refusal of the United States to put pressure on them to do so”.

The “solution to the Donbas dispute lies in the ‘Minsk II’ agreement, reached in February 2015 by the leaders of France, Germany, Russia, and Ukraine meeting under the auspices of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe”; the “key military element of Minsk II is the disarmament of the separatists and the withdrawal of Russian ‘volunteer’ forces, together with a vaguely worded suggestion for the temporary removal the Ukrainian armed forces (exclusive of border guards)”; the “key political element consists of three essential and mutually dependent parts”, namely (1) demilitarization, (2) “a restoration of Ukrainian sovereignty, including control of the border with Russia”, and (3) “full autonomy for the Donbas in the context of the decentralization of power in Ukraine as a whole”; the “Minsk II Protocol was endorsed unanimously by the UN Security Council, including the United States”; “Samantha Power, then US ambassador to the United Nations, told the Security Council in June 2015” that the “‘consensus here, and in the international community, remains that Minsk’s implementation is the only way out of this deadly conflict’”; regarding the Trump and Biden administrations, both “subsequent US administrations have officially supported the Minsk II Protocol”; the “settlement envisioned by Minsk II has not come to pass”; and three “intertwined issues have so far blocked implementation”, namely (A) “the inability to reach agreement between Kiev, Moscow, and the separatist leadership on the terms of permanent Donbas autonomy”, (B) “the sequence in which the establishment of local autonomy and the resumption of Ukrainian control of the border with Russia are to occur”, and (C) “how to secure the long-term autonomy of the region against an attempt by Kiev to impose central control”.

The “Ukrainian parliament did pass a law on special status for part of the Donbas on March 17, 2015, but the law was only provisional, and it was not to come into effect until after Donetsk and Luhansk held elections under Ukrainian law and allowed the restoration of Ukrainian authority”; Ukraine “made no commitment to revise its constitution to provide for decentralization and Russian language rights—moves that are absolutely essential if the inhabitants of the Donbas and other Russian-speaking areas are to feel like full citizens of Ukraine, and which should be insisted upon by the United States and the European Union as a matter of democratic principle”; the “Ukrainian parliament granted far more limited powers to the region than those envisioned under Minsk II”; in “particular, all powers over the police and courts were reserved to the central government in Kiev”; this “limited offer by the previous government of President Petro Poroshenko faced strong opposition in the Ukrainian parliament, and it has effectively been withdrawn by the present administration of President Volodymyr Zelensky”; Zelensky “has declared that Ukraine is not in fact bound to offer permanent autonomy to the Donbas”; and the “Russian government has refused to consider a settlement on these terms”.

A “new US approach to peace in Ukraine should begin with a public restatement by the Biden administration of America’s commitment to the principles of Minsk II in particular, and to the idea of a pluralist, multi-ethnic, and federal Ukrainian republic in general”—it’s “only on this basis that Ukraine can ever be brought back together again and that Ukrainian stability, security, and unity can be guaranteed in the long term”.

Repeated “opinion polls in the Donbas and (before 2014) free elections there indicated that many of its inhabitants favored autonomy for the region within Ukraine and that equally large majorities in eastern and southern Ukraine favored a multi-ethnic state with official status for the Russian language and culture, not the ethnic-nationalist state promoted since 2014 by a succession of Ukrainian governments backed by the West”; between “independence in 1991 and the revolution in 2014, Ukraine was evenly balanced between supporters of an ethnic version of Ukrainian identity in the country’s western and central regions, and supporters of a civic version (with a strong guaranteed role for the Russian language and culture) in the east and south”; the “events of 2014, and the conflict with Russia that followed, have led to a situation in which ethnic nationalists (with Western backing) dominate national politics in Kiev”; and these ethnic nationalists’ program “remains highly unpopular in the Russian-speaking areas and is overwhelmingly rejected in the Donbas”.

To “bring about a peace settlement, it is necessary to eliminate or discount the factors that brought about a failure of the Minsk II agreement”; the chief factor “is Ukraine’s refusal to guarantee permanent full autonomy for the Donbas”; the “main reason for this refusal, apart from a general commitment to retain centralized power in Kiev, has been the belief that permanent autonomy for the Donbas would prevent Ukraine from joining NATO and the European Union, as the region could use its constitutional position within Ukraine to block membership”; and the “official US commitment to eventual Ukrainian NATO membership—however empty in real terms—has in turn inhibited the United States from playing a positive role in resolving the conflict”.

The US will—if it “drops the hopeless goal of NATO membership for Ukraine”—“be in a position to pressure the Ukrainian government and parliament to agree to a ‘Minsk III’ by the credible threat of a withdrawal of US aid and political support”; regarding a settlement, the US should promote two main terms, namely (1) a “Ukrainian constitutional amendment establishing the Donbas region as an autonomous republic within Ukraine (including those parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk provinces currently controlled by Ukraine)” and (2) a “constitution for the Donbas Autonomous Republic (including its constitutional relationship with Ukrainian national institutions in Kiev) to be submitted to the people of Donetsk and Luhansk in a referendum supervised and monitored by the UN and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe”; if “a majority of voters in the Donbas oppose the constitutional amendment, then they will have chosen to remain within Ukraine under its present unitary constitution”; “in the likely event of approval in the referendum, the amendment would then be submitted to the Ukrainian parliament”; and if “the parliament rejected it, a new internationally supervised referendum would be held giving the people of the region a straight choice between rejoining a unitary Ukraine and becoming independent, with a future option to join the Russian Federation”.

Annexation “is not Russia’s preferred option for the future of the region”; “Moscow could have annexed the Donbas (as it did Crimea) at any time during the past seven years but has refrained from doing so”; “Moscow is determined to defend the Donbas against any attempt at Ukrainian reconquest”; “for good political and strategic reasons, it would much prefer that the Donbas remain a pro-Russian autonomous part of Ukraine”; and “if Ukraine launches a new war, annexation will certainly follow, leading to a new crisis in Russia’s relations with the West”.

Ukraine must take “control of the border with Russia” only after “the referendum on autonomy and the establishment of a regional government under the Ukrainian constitution”; this is important in “order to secure the establishment and maintenance of autonomy”; the “police and courts in the Donbas Autonomous Republic would come under the regional government”; military “security would be provided by a UN peacekeeping force drawn from neutral countries outside Europe and established as part of a Security Council resolution in support of the peace settlement”; “US and NATO forces would not be included, nor would Russian forces or those of countries allied to Russia”; and this “peacekeeping force would also supervise and certify the disarmament of the existing separatist armed forces, the withdrawal of all Russian forces, and the withdrawal of the Ukrainian armed forces from their present positions in Donetsk and Luhansk”.

The “United States, of course, has a federal system, as do Canada, Australia, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, India, and South Africa”; there “can thus be no objection from democratic principle to a federal system for Ukraine, or to special autonomy for the Donbas”; given “the vast differences in language and culture between different parts of Ukraine, a federal constitution would seem the best political system for the country as a whole”; failing “that, ‘asymmetric federations,’ in which certain regions enjoy special status or one autonomous region exists in an otherwise unitary state, are also an accepted part of certain democracies”; the “‘Good Friday’ peace agreement of 1998 that brought an end to the Northern Ireland conflict is especially pertinent to a solution to the Donbas conflict”; and this “agreement has also been widely suggested as the only possible model for an eventual settlement of the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan and the unrest in the Indian portion of that territory”.

Ideally “a peace settlement would also include a treaty establishing Ukrainian neutrality for the next generation, modeled on the Austrian State Treaty and associated Austrian law on neutrality of 1955, but to be ended or renewed after 30 years”; though “not strictly necessary, such a treaty would remove the greatest motive by far for Russian interference in and intimidation of Ukraine”; “Ukraine and the United States would sacrifice nothing by such a treaty, since it is impossible for Ukraine to join NATO so long as the Donbas conflict and Crimean dispute remain open”; “the treaty would be a barrier against any future Russian attempt to dominate Ukraine, for it would also rule out Ukrainian membership in any Russian-dominated alliance”; this “treaty would therefore prevent Russia from repeating its bid to draw Ukraine into the Eurasian Union, an attempt that provided the initial spark for the Ukrainian revolution of 2013–14”; from “Moscow’s point of view, this would be a blow”, since “Ukrainian membership is essential to any hope of making the Eurasian Union into a serious international bloc”; “Ukrainian membership in NATO and the EU, far from strengthening those bodies, would in fact drastically weaken them”; on “balance, therefore, Ukrainian neutrality would disadvantage Russia more than the West”; as “for Ukrainian membership in the EU, this is ruled out for at least a generation to come by Ukraine’s corruption, political dysfunction, and lack of economic progress”; the “deep internal problems of the EU also make Ukrainian membership in the near to medium term quite implausible”; at “$285 million a year (in 2020), US economic development aid to Ukraine does not begin to meet Ukrainian needs, let alone help prepare the country for EU membership”; the “miserable examples of corruption in the new EU member states of Bulgaria, Romania, and Slovakia, and of chauvinist authoritarianism in Hungary and Poland, also make it exceptionally unlikely that the EU would seek a large and impoverished new Eastern member for many years to come”; “Ukrainian politicians might wish to study the examples of Finland, Sweden, and Austria during the Cold War”; and these “states lost nothing through neutrality and developed as prosperous, law-abiding, democratic Western societies that were able to join the EU after the Cold War ended”.

The “Minsk proposal for a solution to the Donbas conflict ignores the other territorial dispute between Russia and Ukraine, the Russian annexation of Crimea”; since “Russia has annexed Crimea (in accordance, it seems, with the wishes of a majority of the region’s population), no Russian government can give it up short of decisive defeat in war”; and like “other such issues in the world (Kashmir and Kosovo, for example), this question will simply have to be shelved until it is either quietly forgotten or fundamental changes in the international scene permit its solution”.

These “proposals will meet with strong opposition from Ukrainian nationalists and their supporters in the West, including some in the US Congress”; such “opponents, however, have a duty to say what they themselves are proposing as an alternative to a settlement based on the Minsk II Protocol”; “the only basis for a settlement is that of the Minsk II Protocol”; and at “present, the US approach to Ukraine is a zombie policy—a dead strategy that is wandering around pretending to be alive and getting in everyone’s way, because US policy-makers have not been able to bring themselves to bury it”.

Lieven says in a 22 June 2022 Nation piece: regarding “the Donbas republics, France and Germany brokered a very sensible agreement whereby they would become fully autonomous parts of Ukraine”; as “I have argued previously in The Nation, this was the only way in which Ukraine could retain these territories—but Ukraine refused to implement the agreement, fearing that these territories would act as a Russian ‘fifth column’ within Ukraine”; and this “raises the obvious question of why on earth, if the Ukrainian” parliament “and government fear the eastern Donbas so much, they should want it back again”.

The “only solution to these disputes, it seems to me, lies through the United Nations and respect for local democracy—something that has been completely ignored both by Russia and the West”; in “Crimea, a referendum on Russian or Ukrainian sovereignty should be organized by the UN”; in “return, Russia should agree to a similar referendum in Kosovo, where the vast majority of people also clearly support independence from Serbia, just as a majority of Crimeans clearly favor belonging to Russia”; “Moscow’s lifting of its veto would allow Kosovo to be accepted as a member of the United Nations, and would greatly reduce the danger of another disastrous conflict in the Balkans”; the “US argument that there is no parallel between these cases is a piece of legalistic casuistry, which the present head of the CIA, William Burns, acknowledges in his memoirs to be completely empty”; in “the Donbas, a UN peacekeeping force should be established on the whole territory of the two provinces, accompanied by a mission tasked with organizing a referendum there after a fixed period that will allow most refugees to return home”; this “referendum should be on a district-by-district basis”; and the “likely result, it seems logical to assume, will be that most of the people of the separatist republics, who have been bombarded by Ukraine for the past eight years, will opt to remain independent, while the areas that have been invaded and devastated by Russia in the past four months will opt to stay with Ukraine”.

Back “in February and early March, this war could legitimately be seen as an existential one for Ukraine”; the “initial Russian plan was clearly to capture Kyiv and turn Ukraine into a client state”; that “plan was however comprehensively defeated, and given Russian military losses and Western military support for Ukraine, it cannot be revived”; “Ukraine, with Western help, has won a great victory, and secured its freedom to move towards membership of the European Union—and the EU, not NATO, is the truly important institution when it comes to integration into the West”; the “war has now become a struggle over very limited amounts of territory in eastern and southern Ukraine, of a kind miserably familiar from other postcolonial conflicts”; if “it is ever to end, it will have to do so sooner or later through some form of pragmatic compromise”; and the “interests both of Ukraine and of humanity demand that we should seek this compromise now, not after years of suffering and destruction, with dire side effects for the wider world”.

Greene’s Commentary

Bryce Greene writes in his 4 March 2022 FAIR piece: a “major turning point in the US/Ukraine/Russia relationship was the 2014 violent and unconstitutional ouster of President Viktor Yanukovych, elected in 2010 in a vote heavily split between eastern and western Ukraine”; his “ouster came after months of protests led in part by far-right extremists (FAIR.org, 3/7/14)”; weeks “before his ouster, an unknown party leaked a phone call between US officials discussing who should and shouldn’t be part of the new government”; the “US involvement was part of a campaign aimed at exploiting the divisions in Ukrainian society to push the country into the US sphere of influence, pulling it out of the Russian sphere (FAIR.org, 1/28/22)”; in “the aftermath of the overthrow, Russia illegally annexed Crimea from Ukraine, in part to secure a major naval base from the new Ukrainian government”; the “New York Times (2/24/22) and Washington Post (2/28/22) both omitted the role the US played in these events”; and in “US media, this critical moment in history is completely cleansed of US influence, erasing a critical step on the road to the current war”.

In “another response to the overthrow, an uprising in Ukraine’s Donbas region grew into a rebel movement that declared independence from Ukraine and announced the formation of their own republics”; the “resulting civil war claimed thousands of lives, but was largely paused in 2015 with a ceasefire agreement known as the Minsk II accords”; the “deal, agreed to by Ukraine, Russia and other European countries, was designed to grant some form of autonomy to the breakaway regions in exchange for reintegrating them into the Ukrainian state”; unfortunately, “the Ukrainian government refused to implement the autonomy provision of the accords”; Lieven writes in “The Nation (11/15/21)” that the “‘main reason for this refusal, apart from a general commitment to retain centralized power in Kiev, has been the belief that permanent autonomy for the Donbas would prevent Ukraine from joining NATO and the European Union, as the region could use its constitutional position within Ukraine to block membership’”; “Ukraine opted instead to prolong the Donbas conflict, and there was never significant pressure from the West to alter course”; “there were brief reports of the accords’ revival as recently as late January”; “Ukrainian security chief Oleksiy Danilov warned the West not to pressure Ukraine to implement the peace deal”; “Lieven notes that the depth of Russian commitment has yet to be fully tested, but Putin has supported the Minsk accords, refraining from officially recognizing the Donbas republics until last week”; the “New York Times (2/8/22) explainer on the Minsk accords blamed their failure on a disagreement between Ukraine and Russia over their implementation”; this “is inadequate to explain the failure of the agreements, however, given that Russia cannot affect Ukrainian parliamentary procedure”; the “Times quietly acknowledged that the law meant to define special status in the Donbas had been ‘shelved’ by the Ukrainians, indicating that the country had stopped trying to solve the issue in favor of a stalemate”; there “was no mention of the comments from a top Ukrainian official openly denouncing the peace accords”; and nor “was it acknowledged that the US could have used its influence to push Ukraine to solve the issue, but refrained from doing so”.

By “December 2021, US intelligence agencies were sounding the alarm that Russia was amassing troops at the Ukrainian border and planning to attack”; “Putin was very clear about a path to deescalation”; Putin “called on the West to halt NATO expansion, negotiate Ukrainian neutrality in the East/West rivalry, remove US nuclear weapons from non proliferating countries, and remove missiles, troops and bases near Russia”; these “are demands the US would surely have made were it in Russia’s position”; unfortunately, “the US refused to negotiate on Russia’s core concerns”; the “US offered some serious steps towards a larger arms control arrangement (Antiwar.com, 2/2/22)—something the Russians acknowledged and appreciated—but ignored issues of NATO’s military activity in Ukraine, and the deployment of nuclear weapons in Eastern Europe (Antiwar.com, 2/17/22)”; on “NATO expansion, the State Department continued to insist that they would not compromise NATO’s open door policy—in other words, it asserted the right to expand NATO and to ignore Russia’s red line”; “the US has signaled that it would approve of an informal agreement to keep Ukraine from joining the alliance for a period of time”; “this clearly was not going to be enough for Russia, which still remembers the last broken agreement”; the “US instead chose to pour hundreds of millions of dollars of weapons into Ukraine, exacerbating Putin’s expressed concerns”; had “the US been genuinely interested in avoiding war, it would have taken every opportunity to de-escalate the situation”; and the US instead “did the opposite nearly every step of the way”.

In “its explainer piece, the Washington Post (2/28/22) downplayed the significance of the US’s rejection of Russia’s core concerns”; the WaPo piece says that “‘Russia has said that it wants guarantees Ukraine will be barred from joining NATO—a non-starter for the Western alliance, which maintains an open-door policy’”; “NATO’s open door policy is simply accepted as an immutable policy that Putin just needs to deal with”; and this “very assumption, so key to the Ukraine crisis, goes unchallenged in the US media ecosystem”.

Chomsky’s Commentary

Noam Chomsky makes some interesting points—about Ukraine—in this 2 March 2015 interview that was broadcast live:

Chomsky says: it was “a pretty remarkable concession” when Mikhail Gorbachev agreed “to have Germany join a hostile military alliance led by the only superpower”; NATO “moved right up to Russia’s borders” under Clinton despite the concession; there’s “a very natural settlement to this issue”, namely (1) “a strong declaration that Ukraine will” become neutral and (2) “some more or less agreed-upon choices” about “the autonomy of regions”; “those are the basic terms of a peaceful settlement”; and “we have to be willing to accept it” or else “we’re moving towards a very dangerous situation”.

Chomsky says that “US military equipment was taking part in a military parade in Estonia a couple hundred yards from the Russian border”. I found a 24 February 2015 WaPo piece—titled “U.S. military vehicles paraded 300 yards from the Russian border”—that says: “Russia has long complained bitterly about NATO expansion, saying that the Cold War defense alliance was a major security threat as it drew closer to Russia’s borders”; the “anger grew especially passionate after the Baltic states joined in 2004, and Russian President Vladimir Putin cited fears that Ukraine would join NATO when he annexed the Crimean Peninsula in March last year”; “U.S. tanks rolled through the streets of Riga, Latvia, in November for that nation’s Independence Day parade, another powerful reminder of U.S. boots on the ground in the region”; and the “United States has sent hundreds of military personnel to joint NATO exercises in the Baltics”.

And Chomsky refers to a resolution that “the new government in Ukraine” passed—“like 300 to eight or something”—“announcing its intention to take steps to join NATO”. I found a 23 December 2014 NYT piece—titled “Ukraine Vote Takes Nation a Step Closer to NATO”—that says: the “Parliament, firmly controlled by a pro-Western majority, voted overwhelmingly, 303 to 8, to rescind a policy of ‘nonalignment’ and to instead pursue closer military and strategic ties with the West”; former “President Viktor F. Yanukovych, who was toppled in February and fled to Russia after months of protests in Kiev, the capital, pushed Parliament to adopt the policy in 2010, shortly after he took office”; the “law had defined nonalignment as ‘nonparticipation of Ukraine in the military-political alliances’”; and the “revised law, which was a priority of President Petro O. Poroshenko, requires Ukraine to ‘deepen cooperation with NATO in order to achieve the criteria required for membership in this organization’”.

Cohen’s Commentary

Stephen F. Cohen talks—in his 2019 book War With Russia?—about how low discourse has sunk. He says in the first chapter, which is an abridged version of his 27 August 2014 Nation article:

I want to speak generally about this dire situation—almost certainly a fateful turning point in world affairs—as a participant in what little mainstream media debate has been permitted but also as a longtime scholarly historian of Russia and of US-Russian relations and informed observer who believes there is still a way out of this terrible crisis.

Regarding my episodic participation in the very limited mainstream media discussion, I will speak in a more personal way than I usually do. From the outset, I saw my role as twofold.

Recalling the American adage “There are two sides to every story,” I sought to explain Moscow’s view of the Ukrainian crisis, which is almost entirely missing in US mainstream coverage. What, for example, did Putin mean when he said Western policy-makers were “trying to drive us into some kind of corner,” “have lied to us many times” and “have crossed the line” in Ukraine? Second, having argued since the 1990s, in my books and Nation articles, that Washington’s bipartisan Russia policies could lead to a new Cold War and to just such a crisis, I wanted to bring my longstanding analysis to bear on today’s confrontation over Ukraine.

As a result, I have been repeatedly assailed—even in purportedly liberal publications—as Putin’s No. 1 American “apologist,” “useful idiot,” “dupe,” “best friend,” and, perhaps a new low in immature invective, “toady.” I expected to be criticized, as I was during nearly twenty years as a CBS News commentator, but not in such personal and scurrilous ways. (Something has changed in our political culture, perhaps related to the Internet, but I think more generally.)

Until now, I have not replied to any of these defamatory attacks. I do so today because I now think they are directed at many of us in this room and indeed at anyone critical of Washington’s Russia policies, not just me.…

None of these character assassins present any factual refutations of anything I have written or said. They indulge instead in ad hominem slurs based on distortions and on the general premise that any American who seeks to understand Moscow’s perspectives is a “Putin apologist” and thus unpatriotic. Such a premise only abets the possibility of war.

Some of these writers, or people who stand behind them, are longtime proponents of the twenty-year US policies that have led to the Ukrainian crisis. By defaming us, they seek to obscure their complicity in the unfolding disaster and their unwillingness to rethink it. Failure to rethink dooms us to the worst outcome.

Equally important, these kinds of neo-McCarthyites are trying to stifle democratic debate by stigmatizing us in ways that make our views unwelcome on mainstream television and radio broadcasts and op-ed pages—and to policy-makers. They are largely succeeding.

Cohen says that something “has changed in our political culture, perhaps related to the Internet, but I think more generally”. And that there’s an effort “to stifle democratic debate”.

He says—in the same chapter—that the following things aren’t true: (1) the agreement that the EU—with US backing—offered Yanukovych in November 2013 was “a benign association with European democracy and prosperity”; (2) “Yanukovych was prepared to sign the agreement, but Putin bullied and bribed him into rejecting it”; (3) thus “began Kiev’s Maidan protests and all that has since followed”; (4) today’s “civil war in Ukraine was caused by Putin’s aggressive response to the peaceful Maidan protests against Yanukovych’s decision”; and (5) the “only way out of the crisis is for Putin to end his ‘aggression’ and call off his agents in southeastern Ukraine”.

He says—regarding (1), (2), and (3)—that the facts are the following: the “EU proposal was a reckless provocation compelling the democratically elected president of a deeply divided country to choose between Russia and the West”; so “too was the EU’s rejection of Putin’s counterproposal for a Russian-European-American plan to save Ukraine from financial collapse”; on “its own, the EU proposal was not economically feasible”; offering “little financial assistance, it required the Ukrainian government to enact harsh austerity measures and would have sharply curtailed its longstanding and essential economic relations with Russia”; nor “was the EU proposal entirely benign”; it “included protocols requiring Ukraine to adhere to Europe’s ‘military and security’ policies—which meant in effect, without mentioning the alliance, NATO”; and “it was not Putin’s alleged ‘aggression’ that initiated today’s crisis but instead a kind of velvet aggression by Brussels and Washington to bring all of Ukraine into the West, including (in fine print) into NATO”.

He says—regarding (4)—that the facts are the following: in “February 2014, the radicalized Maidan protests, strongly influenced by extreme nationalist and even semi-fascist street forces, turned violent”; hoping “for a peaceful resolution, European foreign ministers brokered a compromise between Maidan’s parliamentary representatives and Yanukovych”; it “would have left him as president, with less power, of a coalition reconciliation government until early elections in December”; within “hours, violent street fighters aborted the agreement”; “Europe’s leaders and Washington did not defend their own diplomatic accord”; minority “parliamentary parties representing Maidan and, predominantly, western Ukraine” formed the new government after Yanukovych fled; among these minority parties was “Svoboda, an ultranationalist movement previously anathematized by the European Parliament as incompatible with European values”; “Washington and Brussels endorsed the coup and have supported the outcome ever since”; the “February coup” triggered everything “that followed, from Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the spread of rebellion in southeastern Ukraine to the civil war and Kiev’s ‘anti-terrorist operation’”; and “Putin’s actions were mostly reactive”.

And he says—regarding (5)—that the facts are the following: the “underlying causes of the crisis are Ukraine’s own internal divisions, not primarily Putin’s actions”; the “essential factor escalating the crisis has been Kiev’s ‘anti-terrorist’ military campaign against its own citizens, mainly in Luhansk and Donetsk”; “Putin influences and no doubt aids the Donbass ‘self-defenders’”; considering “the pressure on him in Moscow, he is likely to continue to do so, perhaps even more directly, but he does not fully control them”; if “Kiev’s assault ends, Putin probably can compel the rebels to negotiate”; and “only the Obama administration can compel Kiev to stop, and it has not done so”.

Twenty “years of US policy have led to this fateful American-Russian confrontation”; “Putin may have contributed to it along the way, but his role during his fourteen years in power has been almost entirely reactive”; and regarding Putin’s reactiveness, it’s “a complaint frequently directed against him by more hardline forces in Moscow”.

In “politics as in history, there are always alternatives”; the “Ukrainian crisis could have at least three different outcomes”; the worst one would be that the “civil war escalates and widens, drawing in Russian and possibly NATO military forces”; in “the second outcome, today’s de facto partitioning of Ukraine becomes institutionalized in the form of two Ukrainian states”; the “best outcome would be the preservation of a united Ukraine”; this third and best outcome “will require good-faith negotiations between representatives of all of Ukraine’s regions, including leaders of the rebellious southeast, probably under the auspices of Washington, Moscow, the European Union, and eventually the UN”; “Putin and his foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, have proposed this for months”; “Ukraine’s tragedy continues to grow”; thousands “of innocent people have already been killed or wounded”; “there is no wise leadership in Washington”; “President Barack Obama has vanished as a statesman in the Ukrainian crisis”; “Secretary of State John Kerry speaks publicly more like a secretary of war than as our top diplomat”; the “Senate is preparing even more bellicose legislation”; the “establishment media rely uncritically on Kiev’s propaganda and cheerlead for its policies”; and “American television rarely, if ever, shows Kiev’s military assaults on Luhansk, Donetsk, or other Ukrainian rebel cities, thereby arousing no public qualms or opposition”.

And Cohen makes—in a 13 November 2019 interview with an organization that I happen to find extremely problematic but that I think has done good interviews—some interesting observations. Quoting from the transcript: “ultimately you have a situation now which seems not to be widely understood, that the new president of Ukraine, Zelensky, ran as a peace candidate”; this “is a bit of a stretch and maybe it doesn’t mean a whole lot to your generation, but he ran a kind of George McGovern campaign”; the “difference was McGovern got wiped out and Zelensky won by, I think, 71, 72 percent”; he “won an enormous mandate to make peace”; “that means he has to negotiate with Vladimir Putin”; “what’s important and not well reported here” is that “his willingness to deal directly with Putin” actually “required considerable boldness”, since “there are opponents of this in Ukraine and they are armed”; some “people say they’re fascists but they’re certainly ultra-nationalist, and they have said that they will remove and kill Zelensky if he continues along this line of negotiating with Putin”; “his life is being threatened literally by a quasi-fascist movement in Ukraine”; “he can’t go forward with full peace negotiations with Russia, with Putin, unless America has his back”; and maybe “that won’t be enough, but unless the White House encourages this diplomacy, Zelensky has no chance of negotiating an end to the war, so the stakes are enormously high”.

Since “the end of the Soviet Union”, Washington’s stated policy has been to promote democracy—and “particularly constitutionalism”—“in the former Soviet territories”; Yanukovych “had been by all ratifying European monitoring organizations freely and fairly elected”; it “had been a fairly clean election”; “he had already agreed to move elections up”; “I think within nine months you could vote him out”; the 2014 overthrow was “essentially a street coup”; Obama supported Yanukovych’s overthrow “within hours”; it was “a turning point” and “a very important moment”; it was “a blow to constitutionalism, the very cause that we claimed to be promoting, so we need to think about that”; and Obama’s support “sent a message about what the United States really was prepared to” say.

Abelow’s Commentary

Benjamin Abelow writes in his 2022 book How the West Brought War to Ukraine: in “the months since Russia invaded Ukraine, the explanation offered for America’s involvement has changed”; what “had been pitched as a limited, humanitarian effort to help Ukraine defend itself has morphed to include an additional aim”, namely “to degrade Russia’s capacity to fight another war in the future”; “a humanitarian effort would seek to limit the destruction and end the war quickly”; “the strategic goal of weakening Russia requires a prolonged war with maximum destruction, one that bleeds Russia dry of men and machine on battlefield Ukraine”; “America’s new military objective places the United States into a posture of direct confrontation with Russia”; and now “the goal is to cripple a part of the Russian state, its military”.

The “underlying cause of the war lies not in an unbridled expansionism of Mr. Putin, or in paranoid delusions of military planners in the Kremlin, but in a 30-year history of Western provocations, directed at Russia, that began during the dissolution of the Soviet Union and continued to the start of the war”. Abelow writes—regarding this history—that Washington has done the following things either on its own or with European allies:

Expanded NATO over a thousand miles eastward, pressing it toward Russia’s borders, in disregard of assurances previously given to Moscow

Withdrawn unilaterally from the Antiballistic Missile Treaty and placed antiballistic launch systems in newly joined NATO countries. These launchers can also accommodate and fire offensive nuclear weapons at Russia, such as nuclear-tipped Tomahawk cruise missiles

Helped lay the groundwork for, and may have directly instigated, an armed, far-right coup in Ukraine. This coup replaced a democratically elected pro-Russian government with an unelected pro-Western one

Conducted countless NATO military exercises near Russia’s border. These have included, for example, live-fire rocket exercises whose goal was to simulate attacks on air-defense systems inside Russia

Asserted, without pressing strategic need, and in disregard of the threat such a move would pose for Russia, that Ukraine would become a NATO member. NATO then refused to renounce this policy even when doing so might have averted war

Withdrawn unilaterally from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, increasing Russian vulnerability to a U.S. first strike

Armed and trained the Ukrainian military through bilateral agreements and held regular joint military training exercises inside Ukraine. The goal has been to produce NATO-level military interoperability even before formally admitting Ukraine into NATO

Led the Ukrainian leadership to adopt an uncompromising stance toward Russia, further exacerbating the threat to Russia and putting Ukraine in the path of Russian military blowback

Abelow lists those eight things that Washington has done during the past three decades. And he writes:

Although it is impossible to know the specific motivations that led Mr. Putin to invade Ukraine, a combination of factors was likely at play: (1) the ongoing arming, training to NATO standards, and integration of the military structures of Ukraine, the United States, and other Western powers through non-NATO arrangements; (2) the ongoing threat that Ukraine would be admitted to NATO; and (3) concern about possible new intermediate-range missile deployments, exacerbated by a concern that the U.S. might deploy Aegis, offensive-capable ABM launchers in Ukraine regardless whether Ukraine was yet a member of NATO.

He lists three factors—the de facto integration of Ukraine into NATO, the possibility of Ukraine’s formal entry into NATO, and the issue of “intermediate-range missile deployments” and “offensive-capable ABM launchers”.

Abelow asks who: “bears responsibility for the humanitarian disaster in Ukraine, for the death of thousands of Ukrainians, both civilians and soldiers, and for the impressment of Ukrainian civilians into the military”; “bears responsibility for the destruction of Ukrainian homes and businesses, and for the refugee crisis that is now adding to the one from the Middle East”; “bears responsibility for the deaths of thousands of young men serving in the Russian military, most of whom surely believe, like their Ukrainian counterparts, that they are fighting to protect their nation and their families”; “bears responsibility for the ongoing harm being inflicted on the economies and citizens of Europe and the United States”; “will bear responsibility if disruptions in farming lead to famine in Africa, a continent that depends heavily on the importation of grain from Ukraine and Russia”; and “will bear responsibility if the war in Ukraine escalates to a nuclear exchange, and then becomes a full-scale nuclear war”. In “a proximal sense, the answer to all these questions is simple”, namely that “Mr. Putin is responsible”; he “started the war and, with his military planners, is directing its conduct”; and he “did not have to go to war”.

The “provocations that the United States and its allies have directed at Russia are policy blunders so serious that, had the situation been reversed, U.S. leaders would long ago have risked nuclear war with Russia”; “the United States and its European allies have implied that a rational actor would be assuaged by the West’s statements of benign intention”; the implication has been “that the weapons, training, and interoperability exercises, no matter how provocative, powerful, or close to Russia’s borders, are purely defensive and not to be feared”; “the West has suggested that Mr. Putin is imagining strategic threats where none in fact exist”; this “Western framing—which posits a lack of legitimate Russian security concerns coupled with implied and explicit accusations of irrationality—underlies much of the currently dominant narrative”; and this framing “also underlies the ideological position of the Russia hawks who play such a prominent role in Washington”.

The “war in Ukraine probably would not have taken place” had Washington and its NATO allies: “not pushed NATO to the border of Russia”; “not deployed nuclear-capable missile launch systems in Romania and planned them for Poland and perhaps elsewhere as well”; “not contributed to the overthrow of the democratically elected Ukrainian government in 2014”; “not abrogated the ABM treaty and then the intermediate-range nuclear missile treaty, and then disregarded Russian attempts to negotiate a bilateral moratorium on deployments”; “not conducted live-fire exercises with rockets in Estonia to practice striking targets inside Russia”; “not coordinated a massive 32-nation military training exercise near Russian territory”; “not intertwined the U.S. military with that of Ukraine”; and “etc. etc. etc.”. Abelow “would suggest that had any two or three of the many provocations discussed here not occurred, things would be very different today”.

Washington’s words and actions “may have led Ukrainian leaders, and the Ukrainian people, to adopt intransigent positions toward Russia”; instead “of pressing and supporting a negotiated peace in the Donbas between Kiev and pro-Russian autonomists, the United States encouraged strongly nationalistic forces in Ukraine”; and Washington “poured weapons into Ukraine, stepped up military integration and training with the Ukrainian military, refused to renounce plans to incorporate Ukraine into NATO, and may have given the impression to the Ukrainian leaders and people that it might directly go to war with Russia on Ukraine’s behalf”.

Washington’s words and actions “may have affected Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, who won his 2019 election, with over 70 percent popular support, running on a peace platform”; “in the end he failed to carry through”; even “with war looming, he would not compromise for the sake of peace”; shortly “after Zelensky was elected in 2019, Stephen F. Cohen suggested in an interview that Zelensky would need the active support of the United States to overcome pressure—including threats against his life—from Ukraine’s far right”; without “this support, Cohen predicted, Mr. Zelensky would not be able to seek peace”; and to “my knowledge, Zelensky never received any substantial American support to pursue his peace agenda”.

Zelensky “met in Munich with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz” five days before the 2022 invasion—according “to the Wall Street Journal, Scholz proposed to broker a peace deal”. Abelow quotes the following from a 1 April 2022 WSJ piece, which says that Scholz told Zelensky:

that Ukraine should renounce its NATO aspirations and declare neutrality as part of a wider European security deal between the West and Russia. The pact would be signed by Mr. Putin and Mr. Biden, who would jointly guarantee Ukraine’s security.

Mr. Zelensky said Mr. Putin couldn’t be trusted to uphold such an agreement and that most Ukrainians wanted to join NATO. His answer left German officials worried that the chances of peace were fading.

Zelensky “said Mr. Putin couldn’t be trusted to uphold such an agreement and that most Ukrainians wanted to join NATO”—his “answer left German officials worried that the chances of peace were fading”. And Abelow writes:

In a recent interview, Richard Sakwa suggested that Mr. Zelensky could have made peace with Russia by speaking just five words: “Ukraine will not join NATO.” Sakwa continued: “If Putin was bluffing [about the decisive importance of NATO expansion], call his bluff. Instead…we had this catastrophic war.…It was a frivolous approach to the fate of a nation and, above all, the fate of his own people.”

Abelow quotes Sakwa’s observation that Zelensky never tried to avoid war. And Sakwa’s criticism that not trying was “‘a frivolous approach’”.

My Own Thoughts

I think that all of these commentaries—that I’ve quoted from—show that the media gives people a very simple story that doesn’t line up with the actual record. Russia hawks will tell you: (1) Yanukovych was overthrown in 2014 in an event that wasn’t a coup, (2) Russia then illegally annexed Crimea and illegally invaded the Donbas, (3) this Russian response demonstrated that Russia was committed to aggression, and (4) the right path forward was—given (3)—to integrate Ukraine into NATO and forget about doing diplomacy with the Kremlin.

I think that (1) is false. Ukraine had a democratic constitution—it wasn’t a dictatorship. People overthrew an elected official—that’s called a coup. It remains a coup even if you think that there was something wrong with the election—election results can be challenged in court. And it’s not just that Yanukovych’s overthrow was a coup—it looks like he’d been fairly elected and that he was willing to hold early elections.

I think that (2) is true. It’s interesting to note Western hypocrisy on the topic of international law—Westerners who condemn Russia’s illegal behavior shouldn’t ignore their own governments’ illegal behavior.

I think that (3) is incorrect. Russia’s actions had a context around them—that doesn’t make the actions less illegal, but does affect how one should view those actions. Look at the fact that Russia’s only warm-water naval base is in Crimea. And look—see above the quotes from Matlock and also from Quigley—at the whole history of Crimea. Consider Russia’s security interests, the fact that a Washington-backed coup had just taken place, and the issue of how anti-Russia and dedicated to ethnic nationalism and opposed to local autonomy the new government was. I can’t speak to what the Kremlin thought about the extent to which the US had been involved in the coup—I don’t know what the leaked phone call actually demonstrates—but that’s potentially another component. I think that this notion—that Russia proved itself to be committed to aggression—requires you to strip away the context of the actions.

I find it incredibly disturbing to see Russian actions being presented to people context-free—why negotiate with the Kremlin if they’re committed to aggression and annexation and conquest? Isn’t negotiation appeasement—and isn’t war the only option—if Putin is Hitler? Russia has—for 30 years—made it absolutely clear that Ukraine is a red line regarding NATO. The highest-level US analysts have—for 30 years—pointed out that Ukraine is a Russian red line regarding NATO. We’ve known for a long time about the Kremlin’s view on how Ukraine connects to Russian security interests—the 2022 invasion was a major war crime but doesn’t necessarily mean that Moscow poses a threat to other countries.

And I think that (3) was incorrect, so naturally I think that (4) was a catastrophically irrational conclusion to draw. There wasn’t any good reason to think that Putin was Hitler or that diplomacy was impossible—it was unnecessarily provocative to pursue NATO integration and to give up on diplomacy. Integrating Ukraine into NATO was—frankly—a fine way to ensure Ukraine’s destruction and possibly far worse.

Great and well balanced summary of this tragic situation. The US is willing to fight down to the last Ukranian and any voice for a pragmatic settlement is pro-Putin treachery!

Excellent article that provides insight into many of the historical, cultural and geographical factors that led up the current conflict in Ukraine. Learned a lot from reading it and now look at this whole situation with a more informed perspective.