ICEBERG AHEAD

An interview with Paul Jay.

Paul Jay is a journalist and filmmaker—he’s the founder and host of theAnalysis.news.

We live in dark times, and it’s bleak to discuss the prospect that our species will commit suicide, but we should always have “pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will”. Antonio Gramsci wrote the following in 1929—from his prison cell—about the way that pessimism of the intellect coexists with optimism of the will:

You must realize that I am far from feeling beaten…it seems to me that…a man ought to be deeply convinced that the source of his own moral force is in himself—his very energy and will, the iron coherence of ends and means—that he never falls into those vulgar, banal moods, pessimism and optimism. My own state of mind synthesises these two feelings and transcends them: my mind is pessimistic, but my will is optimistic. Whatever the situation, I imagine the worst that could happen in order to summon up all my reserves and will power to overcome every obstacle.

This interview covers dark topics, but I finish off this interview with a section called “Hope”.

Jay generously posted video of this interview on theAnalysis.news—you can see the videos here:

I was honored/thrilled to interview Jay. See below my interview with him, which I edited for flow, organized by topic, and added hyperlinks to. Jay and I edited the transcript based on post-interview discussion, so you’ll notice that the text below doesn’t align with the video of the interview.

Please make sure to subscribe if you like my pieces because that means a lot to me and helps me to thrive on Substack! Enter your email and click this button—that way you’ll get an email whenever I publish a piece:

Before we plunge into the interview, make sure to read this important interview in which Chomsky makes these harrowing comments:

The basic facts are brutally clear, more so with each passing year. They are laid out clearly enough in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, released on August 9. In brief, any hope of avoiding disaster requires taking significant steps right away to reduce fossil fuel use, continuing annually with the goal of effectively phasing out fossil fuel use by mid-century. We are approaching a precipice. A few steps more, and we fall over it, forever.

Falling off the precipice does not imply that everyone will die soon; there’s a long way down. Rather, it means that irreversible tipping points will be reached, and barring some now-unforeseen technological miracle, the human species will be entering a new era: one of inexorable decline, with mounting horrors of the kind we can easily depict, extrapolating realistically from what already surrounds us—an optimistic estimate, since non-linear processes may begin to take off and dangers lurk that are only dimly perceived.

It will be an era of “sauve qui peut”—run for your lives, everyone for themselves, material catastrophe heightened by social collapse and wholesale psychic trauma of a kind never before experienced. And on the side, an assault on nature of indescribable proportions.

All of this is understood at a very high level of confidence. Even a relic of rationality tells us that it is ridiculous to take a chance on its being mistaken, considering the stakes.

This comment about “wholesale psychic trauma” really shook me, so I’ll quote it again so that everyone can read it carefully and visualize what’s ahead if we choose inaction over action:

It will be an era of “sauve qui peut”—run for your lives, everyone for themselves, material catastrophe heightened by social collapse and wholesale psychic trauma of a kind never before experienced. And on the side, an assault on nature of indescribable proportions.

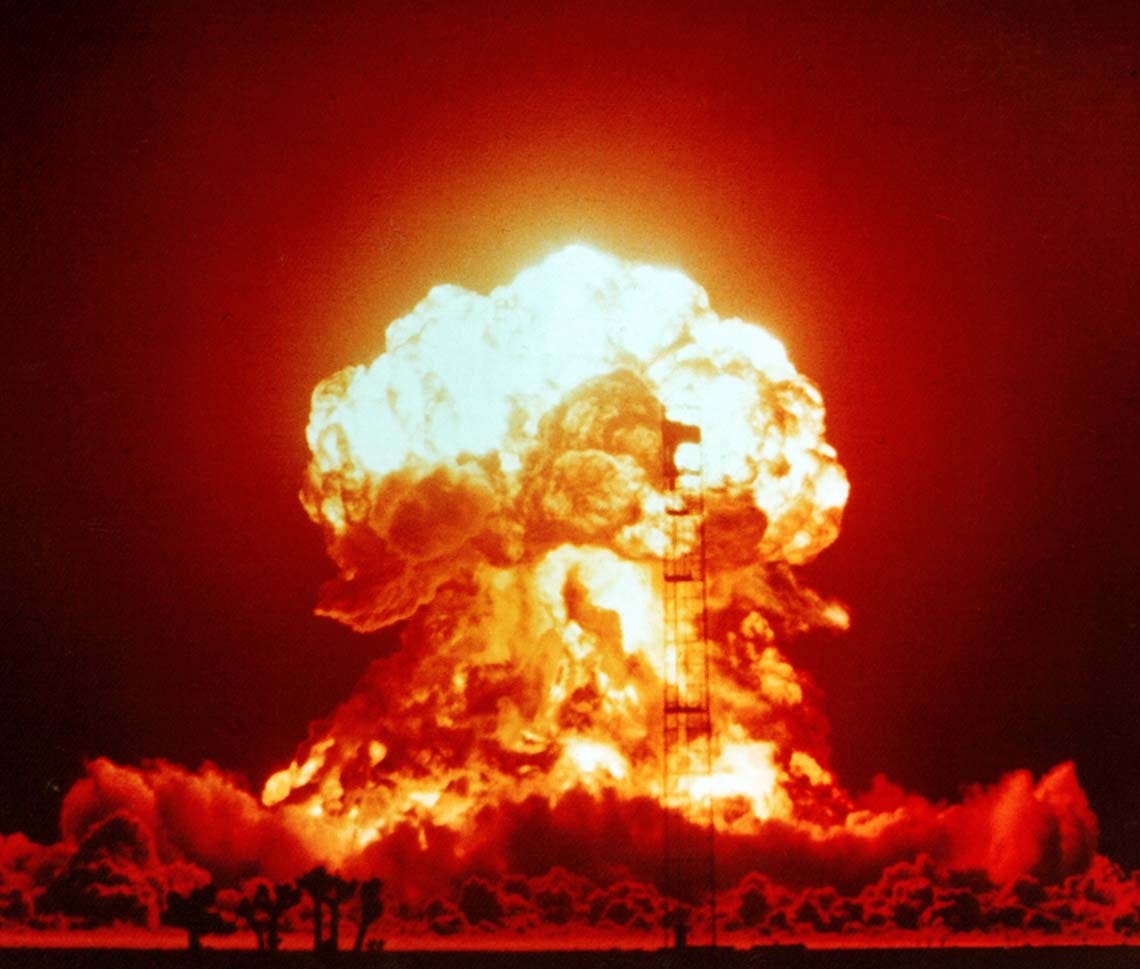

Nuclear Weapons

1) What are the most exciting projects that you’re currently working on?

People know theAnalysis.news—I find that exciting because I get to talk to great brains all the time.

But I’m also working with Daniel Ellsberg on a project based on his book The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner. We hope to turn it into a four- or five-part series for one of the major platforms—I’ve already done 15–20 hours of interviews, and I’m about to go back to Berkeley to do some more.

It’s an exciting project because I get to work with Ellsberg, who’s one of the great people of our time—he’s a great brain and he was on his way to becoming a Nobel laureate in economics before he went into military strategy and later released the Pentagon Papers.

But it’s also a terrifying project—he has me quite convinced that it’s quite a miracle that humans are still living on this planet and that we have to treat nuclear weapons as a threat on the same level as the climate crisis, which means that we really face a dual existential threat.

His book is about when he worked for RAND Corporation advising the Pentagon on American nuclear war strategy—he writes about what he calls “institutional madness”, and the book captures the harrowing tales of how close we’ve come to blowing the Earth up. But I shouldn’t really say “we”, since most of us have no say in the matter—it’s the elites in the United States who’ve been the principal drivers of nuclear weapons. And Ellsberg discovered that those elites to a large extent pushed the Soviet Union into a big investment in nuclear weapons—the Soviets weren’t planning to do it, but one of the Cold War’s big lies was that the Soviets were way ahead in ICBMs, and Ellsberg found out that that wasn’t true.

2) I think there’s a common perception that things aren’t as bad as they used to be with nuclear weapons—everyone agrees that the Cuban Missile Crisis was extremely close, but people have a perception that it’s not as big of a threat today. What do you make of that?

It’s as bad as climate denial—it’s the same phenomenon as climate crisis denial.

The nuclear threat is as dangerous—or maybe more dangerous—than it’s ever been.

On the whole, as batshit crazy as much of the US military leadership was, the political leadership in the USSR and the US was rational—rational in the sense that they didn’t want to blow the world up, despite generals on both sides being willing to strike with nuclear weapons.

One of the Cuban Missile Crisis’s great lessons is that we came very close to being demolished despite the fact that Nikita Khrushchev and John F. Kennedy were both rational people. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, a Soviet submarine was underneath American ships, and the ships dropped signaling depth charges to bring the submarine to the surface. The submarine’s captain tried to launch nuclear weapons on the assumption that nuclear war had broken out, and he needed the political officer to agree to the launch, and the political officer approved. But by sheer chance the flotilla commodore happened to be on that submarine too, and his rank meant that he had to agree as well, and he refused, and an argument broke out, and the flotilla commodore prevailed against the other two and prevented the launch. And the flotilla commodore actually got in shit for it when he went back to Moscow.

There are quite a few examples like this of how close we’ve come.

The arsenal of nuclear weapons is getting bigger—the Americans are already in the midst of spending a trillion dollars over the next 30 years on new weapons, and most of that money will be spent in the first 10 years, and the Russians are also investing more in nuclear weapons. The US will have a whole fleet of Ford-class aircraft carriers that will have nuclear-armed weapons.

China has been very modest in terms of nuclear ICBMs until now—the estimates have been that China has maybe 200 ICBMs compared to the several thousand that the US has and the several thousand that Russia has.

But China now feels very pushed to enhance their own nuclear ICBMs in response to these massive new US and Russian expenditures, and also in response to aggressive US policy toward China. So there’s a new nuclear arms race.

The rivalry and tension between the US and China are very serious—sections of the American elite and American military simply don’t want to accept a world where there’s an equal superpower, but the writing’s on the wall, and China has a huge economy and has all of the ability for innovation and military innovation. So it’s a very dangerous situation, and all the saber-rattling over Taiwan could easily get out of control.

The phenomenon of nuclear winter adds to the danger of all of this—the thinking is that a limited nuclear war will cause all hell to break loose and will inevitably escalate to a total nuclear war, and then ash from all of the burning cities will envelop the Earth and essentially wipe out agriculture and organized human life. Even a nuclear war between India and Pakistan is apparently enough to create a regional nuclear winter, and some studies indicate that a thermonuclear war between India and Pakistan—if India and Pakistan ever developed H bombs—would be enough to create a global nuclear winter:

“Rapidly expanding nuclear arsenals in Pakistan and India portend regional and global catastrophe” (2 October 2019)

The prevailing idea is that it’s not as dangerous as it used to be, and that idea adds to the danger—at least in the past there was widespread recognition, so much so that one of the largest protests that ever happened was a protest in New York against nuclear weapons, but now you barely hear anyone raise their voice. An odd group here and there will do something, but there’s no protest on a scale that could have much impact.

So we’re hoping that this series with Ellsberg will help to wake people up.

3) Does your series with Ellsberg have a title and do you know on which platform it’ll be released?

The title will probably be a variation on his book’s title—it’ll probably be Doomsday Machine: The Confessions of Daniel Ellsberg or something like that.

As for the platform, we haven’t made a deal yet, but there’s interest and we’re talking to a few streaming services and cable channels.

4) Apparently Donald Trump shredded some longstanding nuclear weapons treaties—what effect did that have, and do you know if the Biden administration will reinstate those treaties?

The New START treaty was extended very soon after Biden was inaugurated.

But there’s a crying need for a new round of treaties that will seriously reduce nuclear weapons, and those treaties must include China. And those treaties should also include France, the UK, Pakistan, India, and Israel. And it’s just ridiculous to deny that Israel has nuclear weapons—everybody knows it does and even Jimmy Carter came out and said that Israel has nuclear weapons.

Ellsberg’s message is that these massive numbers of weapons have very little to do with deterrence, especially when you look at how many ICBMs the US and Russia have. And a lot of experts on this say that these weapons are useless for deterrence because the big powers more or less know how to find one another’s ICBMs, and so these ICBMs become targets. The effective deterrence comes from nuclear submarines, and so we should get rid of the vast majority of weapons because the weapons don’t provide any effective deterrence.

Given nuclear winter, you probably only need a far more modest amount of weapons—under 100 weapons, and maybe 10 or 15 weapons even. We should get the numbers down to whatever would provide actual deterrence and also mitigate the threat of accidental nuclear launch.

It’s so logical and rational to have a modest system of genuine deterrence, but the American military–industrial–financial complex makes a lot of money from nuclear weapons and also from the defense systems and the paraphernalia that go with nuclear weapons. And the same profit motive exists in Russia and increasingly in China too where five of the 15 largest arms manufacturers are now based. So the profit motive drives things in US and in Russia and in China, but let me repeat that the US is the most aggressive and that the US pushes Russia and China into more nuclearization.

Other than climate, nuclear weapons are probably the best example of global capitalism’s complete suicidal irrationality, since these people are willing to risk the apocalypse for the sake of money-making—it’s really mind-boggling that they continue to do this when they know how close we’ve come and when they know how far the safeguards are from foolproof.

5) What exactly is the path toward major reductions? The key issue seems to be that countries need to be able to trust one another, and so you can’t ratchet down your arsenal unless you trust that your enemies will do so at the same time. So how can you create a framework in which all these different countries can have some kind of transparent inspection mechanism or something that will allow for actual trust?

I don’t think that’s the barrier—Reagan worked it out with Gorbachev, and Reagan’s famous line was “Trust, but verify”. These countries have good intelligence, and these countries have ways to inspect through the IAEA, and I don’t think that much goes on that’s so secret.

I think the issue is the momentum, strength, power, and logic of massive military expenditures, and also the fact that the US—even though they haven’t nuked anyone since Hiroshima and Nagasaki—likes to be able to threaten and blackmail people.

Donald Trump—and he’s not the only one—was reflecting sections of very senior military leadership when he talked in all seriousness about using tactical nuclear weapons against a non-nuclear country like Iran. The Iranians listening to that must have thought: “We’d better become a nuclear-weapons country if the Americans are serious about the use of tactical nuclear weapons.”

The US economy is so militarized that the economic logic drives the military culture’s logic—military spending rescued the US from the Great Depression, and there was worry that the US economy would become depressed again if stimulus didn’t continue, and so pretexts about the Cold War were advanced in order to keep that stimulus going. But the main motivation for the increased militarization was the extremely high profits from conventional—and also nuclear—arms manufacturing.

Ellsberg started off as a Cold Warrior, but Ellsberg changed his views when he found out that the Cold War stuff was total bullshit. Back in ’59 and ’60, Kennedy and others were talking about the missile gap—the USAF and the Strategic Air Command were saying that the Soviets had 1000 ICBMs and that the US only had 200, and the claim was that there was a danger the Soviets might do a first strike. But when the U-2 spy plane started flying, Ellsberg found out that the real Soviet number wasn’t 1000—it was four. One, two, three, four—four. It was all propaganda! It was the United States that had the first-strike capability, and the Soviets were the ones in a defensive posture based on fear about a first strike from the United States.

It’s important to understand that a section of the US military has always thought that the only long-term way to maintain American dominance is through the annihilation of any major power that threatens to become an equal.

And dangerous US militarization isn’t just about arms companies that want to make money—it also has to do with how financialization and militarization go hand in hand. The financial sector has become absolutely dominant since the 1970s, so you can’t really separate finance from these arms companies. When it comes to Lockheed Martin and Boeing and Raytheon, financial institutions of one kind or another own the majority of the shares, and these financial institutions—especially the asset management companies like BlackRock and Vanguard and State Street—decide who manages these corporations. So the all-powerful financial sector’s interests are inseparable from the military–industrial complex’s interests.

I have an article on my website about the fact that the financial institutions have dominant positions in just about everything on the stock market, and that includes the fossil fuel companies; the arms manufacturers that make nuclear weapons; and all of the major media companies with the exception of Jeff Bezos’s Washington Post and Michael Bloomberg’s Bloomberg. Here’s the article:

It’s not that the US is an evil empire, but rather this is just the way that global capitalism works—you see an opportunity and you take it, and that’s true whether you’re a small business or a big corporation or a state. So if you’re a state and you have the opportunity to become the global hegemon, you take it. If Canada had the chance to become the global hegemon, they’d jump at it.

The problem with nuclear weapons is that the US military is convinced—and enough of America’s elites are convinced—that part of global dominance depends on nuclear-weapon dominance, and it’s insane because you can’t use these weapons without destroying yourself, but somehow this insane logic prevails, even though I can’t understand the mindset where you would risk annihilation.

6) Shouldn’t one submarine or a couple of submarines provide ample deterrence against any country?

It doesn’t take very much—five or 10 submarines should be enough—but the Pentagon doesn’t want to accept the concept of nuclear winter. It’s very much like climate denial. Leading climate scientists have examined what happened to the climate after the fire bombings in Germany and Japan, and they’ve looked at what happens when you get a massive amount of ash from volcanoes, and they’ve concluded that nuclear winter would wipe us all out.

The climate crisis will wipe out global capitalism—maybe rich people think that they’ll be OK for a generation or two, but it won’t be long before most of the Global South is uninhabitable, and so these millions of people will move north to countries that will also eventually become uninhabitable.

So we’ve reached a point now where capitalism’s irrationality is such that—because of climate and also I would say because of nuclear weapons—the system itself just won’t survive this.

And the profit-making imperative is such that the elites know what’s coming and the elites know what has to be done, but the elites simply won’t take the necessary measures, or at least the elites haven’t taken those necessary measures so far.

7) Are countries so tied together economically that there’s an economic form of mutually assured destruction? If the United States was nuked, what would happen to the global economy? Even if Russia was nuked, if any major country was nuked, what would happen to the global economy?

I don’t think that you can frame the question that way because there’s no global economy if nukes begin—organized human society ends with nuclear war. And according to the military strategists I’ve talked to, there’s no such thing as limited nuclear war because once nuclear war breaks out it has its own logic. No country has anything to gain from a first strike, so nobody would deliberately launch a first strike, but there could be an accident—shit happens.

What will the US do if there’s a real confrontation over Taiwan and the US President—mostly because of domestic politics—wants to look tough and sends an aircraft carrier and tells the Chinese to back down? The Chinese have their own domestic politics and their own nationalism and their own military culture, so the Chinese won’t back down, and then do the Americans just back off?

You might think that cooler heads will prevail in these situations, but I was completely convinced that the Americans wouldn’t invade Iraq because every person who knew the situation said that it would be a disaster both for the Iraqi people and for the Americans. And the predictions were correct—it was a disaster for the Iraqi people, and Iran probably has more influence now in Iraq than the Americans do, and China probably has more of the oil now than the Americans do.

But the arms companies and the Halliburtons of the world made a fortune from Iraq. I just read today about a woman named Bunny Greenhouse who was in the Pentagon’s contracts section, and she blew the whistle on the Halliburton contract that was signed not long after Cheney had left Halliburton—it was a no-bid contract for $7 billion to restructure the Iraqi oil industry after the invasion. We know that Cheney had stock options, and he got a big severance payment, and who knows how else he got paid off. So how much of this strategically terrible invasion was just about straightforward money-making?

8) Apparently there’s a profound amount of groupthink among these nuclear planners—apparently these nuclear planners are very bubbled-off and very isolated. Does that yield some of the irrationality behind nuclear planning?

I think there’s also another factor where money-making fuels a profound nihilism and profound cynicism and a bubble of denial.

And the mainstream media didn’t pick up on an important story that I covered about this topic:

Les Earnest worked in one of the first computer sections of the US Army in the late ’50s, and after that MIT hired him to help develop a defense system against Soviet nuclear bombers. Over a trillion dollars was spent on this system over 25 years, and it was a brilliant system, and it was just the system that you see on the big board in Doctor Strangelove where they can track with lights everything coming in. It was the greatest harnessing of computer power in history—there were warehouses and warehouses of computers to control these radar systems.

Earnest had been there about a week before he asked one of his colleagues: “How do you guys solve the radar-jamming problem?” There was a long silence, and then the guy said: “We don’t talk about that.” And then Lester said: “If you don’t solve the problem of radar-jamming, then what’s the point of all this?” And the reality was that the whole thing was bullshit, but they wouldn’t discuss radar-jamming because there was so much money to be made.

And this massive computer system was also supposed to guide Bomarc missiles that would shoot down Soviet aircraft, but radar-jamming made that impossible, but Lester was asked after he’d been working on the system for a year and half to go to Congress to persuade them that the Bomarc missiles should have nuclear weapons on their tips.

I asked Lester: “Hold on—you want to shoot down a Soviet nuclear bomber with a nuclear weapon? So you want to have nuclear weapons blowing up other nuclear weapons over Canada and the United States? That’s your defense strategy? That’s insane.” And Lester told me: “Of course it’s insane.” And I said: “Did you go to the Pentagon and Congress and ask them to do that?” And he said: “I did.” And I asked: “Did they agree?” And he said: “They did. And they did arm Bomarc missiles.” And I said: “Why did you do it?” And he said: “We were all making so much money. We were so cynical. And if we hadn’t done it, somebody else would’ve.”

So that’s the logic: If I don’t do it, somebody else will, so I might as well make some money. He and his colleagues figured: “The world’s going to blow up sooner than later anyway, so what the hell?”

A trillion dollars was spent on a radar system called SAGE, and Robert McNamara had that system studied in the mid-’60s, and the study concluded that the system was nonsense and that the system never would’ve worked.

9) In The Doomsday Machine, Ellsberg gives the following harrowing quote from John H. Rubel’s Doomsday Delayed:

The briefing was soon concluded, to be followed by an identical one covering the attack on China given by a different speaker. Eventually, he too arrived at a chart showing deaths from fallout alone. “There are about 600 million Chinese in China,” he said. His chart went up to half that number, 300 million, on the vertical axis. It showed that deaths from fallout as time passed after the attack leveled out at that number, 300 million, half the population of China.

A voice out of the gloom from somewhere behind me interrupted, saying, “May I ask a question?” General Power turned again in his front-row seat, stared into the darkness and said, “Yeah, what is it?” in a tone not likely to encourage the timid. “What if this isn’t China’s war?” the voice asked. “What if this is just a war with the Soviets? Can you change the plan?”

“Well, yeah,” said General Power resignedly, “we can, but I hope nobody thinks of it, because it would really screw up the plan.”…

That exchange did it. Already oppressed by the briefings up to that point, I shrank within, horrified. I thought of the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, when an assemblage of German bureaucrats swiftly agreed on a program to exterminate every last Jew they could find anywhere in Europe, using methods of mass extermination more technologically efficient than the vans filled with exhaust gases, the mass shootings, or incineration in barns and synagogues used until then. I felt as if I were witnessing a comparable descent into the deep heart of darkness, a twilight underworld governed by disciplined, meticulous and energetically mindless groupthink aimed at wiping out half the people living on nearly one third of the earth’s surface. Those feelings have not entirely abated, even though more than forty years have passed since that dark moment.

There’s another quote from General Power where he says: “Restraint? Why are you so concerned with saving their lives? The whole idea is to kill the bastards. At the end of the war if there are two Americans and one Russian left alive, we win!”

10) These quotes from Power are incredibly harrowing things to read. It sounds like your project with Ellsberg will be fantastic, and I’m very excited to see the series! The two existential threats to organized civilization are global heating and nuclear weapons, but how many people in the public put the issues at the top of the list in terms of political urgency? I don’t know if this summer’s events moved the needle on public opinion on climate. And I would imagine that almost nobody considers nuclear weapons to be a serious issue.

To some extent people in the climate movement—and others—think there’s already so much doomsday talk with climate that you can’t add nuclear. So how do you add nuclear, especially when there’s a pandemic going on?

How can we trust our leaders with nuclear weapons when these people couldn’t properly prepare for—and respond to—a pandemic that they’d been warned about for decades? We’re supposed to trust these people with nuclear weapons? And we’re also supposed to trust these people on the climate side?

There’s been a complete evisceration of the public education system in rural America, and something like 40% of Americans don’t believe in masks or vaccinations, and the same percentage of Americans more or less don’t believe in climate science. And I can’t say that Canada is that much better when it comes to public education.

Certainly in the urban centers people know about climate now. And even in rural America many people know about climate—they’re seeing agricultural effects and forest fires and droughts, so climate’s increasingly on the radar.

But only an infinitesimal fraction of people are focused on nuclear, even in the cities, and even on the left, and even in the most educated sectors.

And some basic steps could be taken. Canada could refuse to have anything to do with nuclear weapons, but they don’t take that stand. And in the US, there could be a massive reduction of weapons and—at the very least—elimination of the hair-trigger mechanism that gives people very little time to decide whether something on the radar is real or not.

Ellsberg has proposed a whole list of things that could be done on nuclear, and in some ways nuclear is way easier to deal with than climate, but the consciousness isn’t there on nuclear.

11) I don’t know how much US presidential debates indicate what’s on the radar, but there wasn’t even a climate debate in the last presidential election—is a nuclear-themed presidential debate even imaginable?

Senator Ed Markey and Rep. Ro Khanna introduced a piece of legislation to stop the new investment in ICBMs, but that legislation got almost no play in the press and it has no legs in Congress.

Global Heating

1) What do you make of the moves in the corporate sector toward support for decarbonization? You talk a lot about BlackRock, and BlackRock’s Larry Fink has a letter where he talks about ESG, so Fink is one of the mascots of the whole corporate ESG movement.

They’re “caught between a BlackRock and a hard place”, so to speak. They get it, and they see the science, but they can’t disrupt capitalist logic:

BlackRock said that they would reduce their investment in coal. But Andrew Ross Sorkin asked Fink: “You’ve got this enormous power to tell the S&P 500 to throw coal out of the index or else you’ll stop investing in the index—why don’t you do that?” And of course Fink had no answer for that because BlackRock makes a lot of money from that index and also because BlackRock just won’t take climate that seriously.

BlackRock also makes discretionary investments where they pick and choose stocks, and Fink said that they won’t invest in any company that makes more than 25% of its revenue from mining coal, so it sounds great when you see all the big coal companies that BlackRock’s going to disinvest from. But Arch Coal is the second-largest coal-mining company in the US, and it makes less than 25% of its revenue from coal, so BlackRock doesn’t have to disinvest in that case. And even if BlackRock did seriously disinvest from coal, other funds would simply buy up the shares and say: “Nice for you, BlackRock—maybe you can afford to get out of coal, but we need the money, so we’re going to get more into coal.”

So it turns out to be smoke and mirrors, and Larry Fink knows that, and there needs to be public intervention to force everyone by law to disinvest from coal—only serious regulation will save us. You can’t rely on tax maneuvers or market mechanisms, although those things are fine as a secondary tactic as long as the primary tactic is real laws that actually phase out fossil fuel.

But the problem is that giving regulators that much power would then open the door to serious regulation of the financial sector, which almost destroyed the global economy and which plunged us into the Great Recession. The whole financial sector is BS anyway, since they rely on public money coming in and bailing them out of their speculative manias, and during the pandemic the Fed massively propped up the stock market to prevent it from collapsing.

So it’s a real conundrum—the elites like the status quo where the state is like the financial sector’s appendage, and the elites don’t want to give that situation up, but the elites know that taking action to save us from climate disaster would require to change that relationship between the state and the financial sector.

There are elites who get it when it comes to climate. Daniel Ellsberg has a great line on the nuclear stuff where he says: “You’ve got to act as if we’re on the Titanic and there’s still time to turn the ship away from the iceberg—you’ve got to hope that the captain will contact the Titanic’s owners and tell them that we’re not going to be in a race, that we’re going to slow down and stop at night and make a safe crossing, and that they can go fuck themselves.”

And I love his metaphor because the Titanic’s owners were actually the ones who wanted to show that it was the fastest boat and that it could do this and that. But of course the ship’s captain never contacted the owners, and the Titanic hit an iceberg and sank, so you can’t put a rosy picture on our situation.

I interviewed a climate scientist who was one of the lead authors of Chapter 11 of the new IPCC report:

And one of his co-authors was quoted when they released the new IPCC report as saying: “What’s the point? It just gets ignored.” She says that it’s not a good use of scientists’ time to do these reports. So I’m not sure how we break through the cultural bubble that exists.

You’ve got a situation where the majority—maybe a slim majority, but a majority—of North America’s population is economically doing OK or doing well, and the section of people who are desperate economically can’t think about anything except how to survive this month, and then the left is very sectarian and there’s a lot of left-wing infighting that goes on and there’s no great national organizing movement in the US or in Canada. So that’s where we are.

2) What about the idea that coal stocks aren’t attractive to investors in this day and age?

Clearly there are lots of investors interested in coal—see this article about coal stocks:

“4 Coal Stocks to Accumulate Right Now Before the Rally Ends” (8 October 2021)

3) How much control do asset management companies like BlackRock really have?

Their assets come from sources that range from pension funds to billionaires, but these asset management companies vote their shares when it comes to annual meetings and special shareholder resolutions:

“Activists thought BlackRock, Vanguard found religion on climate change. Not anymore” (13 October 2019)

4) I interviewed Bob Pollin. He and Chomsky wrote a book called Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal, which Ellsberg said is the roadmap that we need to follow in order to save ourselves—Ellsberg called that book a “survival manual for civilization”. You should never look to elites for anything, really, but do the billionaires understand that a global Green New Deal is needed or else we’re all toast?

They understand that it’s needed, but they’re not doing what it takes to get there. They’ve adopted the rhetoric of net-zero emissions by 2050, but the concept of net-zero emissions is kind of bullshit, since it means that you can have carbon offsets and various tax schemes.

But most importantly, the major countries’ plans to reach net-zero emissions all rely on carbon capture instead of a deliberate, regulated, law-enforced phasing out of fossil fuel. Biden’s plan relies on carbon capture, and elites continue to talk about carbon capture, but carbon capture can’t accomplish enough to reach the targets that the scientists say that we need to hit.

I just read an article today that said that carbon capture might be able to accomplish 20% of the decarbonization that we need to do, but even that 20% is a total question mark and it would take billions and billions and probably trillions of dollars to build up enough carbon-capture capacity to even do that 20%:

“Carbon capture—dream or nightmare—could be coming. Or not.” (30 August 2021)

And everything that I’ve read says that getting to net-zero by 2050 isn’t enough because we won’t stay under 2° by 2050 if we don’t stabilize at 1.5° by 2030.

But based on the interview that I did with the climate scientist and based on the recent IPCC report, people should understand that 1.5° is a disaster.

And on top of that, the climate scientist told me about tipping points where the oceans’ capacity to absorb carbon might decrease in an unexpected way—we can’t estimate the probability that that’ll happen because there’s not enough data. And if that happens, all bets are off and everything goes out the window in terms of how much time we have.

The elites aren’t stupid, and they read the same stuff we read, and I think the majority of the elites have so much wealth that when it really comes down to it they’ll be OK one way or the other. It’s not for nothing that these people are building spaceships and buying land in New Zealand. Rob Johnson knows a lot of these rich people—he says that denial is very comforting, and that you go about your life like most of us do, and that you feel like you’re immune if you have millions and billions of dollars.

Will some individual elites who have a lot of power and influence understand the catastrophic nature of this, understand that they have to actually think about their own children, and understand that protecting your family doesn’t mean that much if the planet goes to hell? I guess we’ll see.

In some ways, everything about capitalism tells us that they won’t take action, but the jury’s out and we’ll find out.

You would’ve hoped for real breakthroughs in places like Brazil and India, but instead you got Bolsonaro and Modi, so we might have to get deep into the shit before enough people wake up and take action, and one hopes it won’t be too little too late.

5) I’m using Larry Fink as a mascot, but it’s one thing for these elites to say that their companies will do X/Y/Z, and it’s another thing for these people to get political and put their billions of dollars into politics in order to push for a global Green New Deal. These elites are very intelligent and very well-informed, and they understand that it’s a serious emergency, so I would expect to see them shift from “My company’s going to do this” to “I’m going to get political now and pour money into politics now and we need to have a global Green New Deal now”.

These elites are very political—Larry Fink’s man is Biden’s economic advisor, and these elites control the corporate Democrats.

We need to take action like it’s war—with World War II there was enormous state intervention to quickly put the country on a war footing, and that’s what’s needed now.

Right now they should obviously nationalize the fossil fuel industry—you could pay all the shareholders (mostly financial institutions) and say: “OK, here’s X trillion dollars. Go away. We now own the fossil fuel industry. You haven’t lost anything. We’re phasing this out.”

I interviewed Bob Pollin a little while ago, and he reckons that you could pay every fossil fuel worker in the US three years of their current wages for $2 billion, which isn’t lunch money for Jeff Bezos and isn’t even detectable for BlackRock. So that means $4 billion for six years of their current wages and $8 billion for 12 years of their current wages and so on—you could guarantee that all the fossil fuel workers wouldn’t lose a dime due to decarbonization, and you could electorally weaken the Republicans in all of these fossil fuel states, since no fossil fuel worker will turn down money to retire early.

So why doesn’t Biden do that? Because that would mean going to war with the fossil fuel companies that the financial sector primarily owns, and the corporate Democrats need financial sector support and funding in order to win elections.

This goes back to on-the-ground organizing because you could organize in fossil fuel states and organize fossil fuel workers and make this early retirement a demand—I think that that would be a successful platform to organize on. And why should fossil fuel workers bear the brunt of something the whole society has participated in?

6) In Canada, can Ottawa just bail out Alberta? Alberta is stupid on climate change because that’s where their bread is buttered, so you just do the same thing with them and bail them out, and then they won’t care and you can move forward on climate.

It’s clear that the writing’s on the wall with the tar sand—the best way to start the transition would be to offer the fossil fuel workers wage subsidies, and that wouldn’t be that much money, and that would definitely electorally weaken Alberta’s right wing.

7) I did a piece on climate communication. And I’ve seen statistics that say that people in America largely agree that global heating is real; largely agree that it’s going to harm people in poor countries like in Africa and so on; largely agree that it’s going to harm their kids; and largely agree that it’s going to harm plants and animals. But apparently the barrier to action is that the poll numbers go way down when you ask people if global heating will harm you personally. But that makes no sense to me—doesn’t everyone, including psychopaths, want their kids to have a good life?

It used to be really alarming how many people answered poll questions the way you described, but I think recent events have really changed the poll numbers because people have been directly affected—look at what happened in New York and New Jersey, and look at the wildfires out west. People are getting it, although there isn’t enough consciousness about what’s really required.

It’s easy to be in denial in the Canadian urban centers, and something like 80% of Canada is urban. I’m in Toronto now, and we’re having a great summer, and people joke that in about 10 or 15 or 20 years we’ll grow mangoes in Muskoka. It’s different out west because the fires have clearly hit people in a way that hasn’t happened before.

Why isn’t there a larger-scale climate movement in Canada? I guess that it doesn’t really affect people yet, even if people say that it does when polled. A majority of people in Toronto have air conditioning. And the significant number of people who can’t afford air conditioning are very marginalized, and aren’t organized, so you don’t hear about them.

On the whole, the media are terrible in Canada and the US—the amount of time spent on the climate crisis is minimal. And there’s very, very little investigative journalism about how ineffective government policy is, so people get fooled very easily and say in response to government claims: “Oh, OK! They’re taking it seriously now!”

8) But it’s incredibly confusing to me because if you have kids or you care about the future of society then you should be in panic mode, even on the most narrow and self-interested grounds and even if you’re a psychopath.

I think psychopaths don’t think very far ahead—they’re stuck inside their most immediate impulses, needs, and logic. And the problem with capitalism is that psychopaths rise to the top who don’t give a damn about society and are totally focused on money-making.

Think about Tony Soprano’s Mafia mentality—everybody in the entire world is expendable for people in the Mafia except maybe their immediate family, and even with their family there’s a narrow money-making logic. But people in the Mafia don’t give a damn about getting people addicted to drugs, or about the destruction that they cause, or about the havoc that they wreak—people in the Mafia just want to make money today, and the rest is somebody else’s problem.

I think most capitalist elites—the people who are actively running the system, whether it’s big corporations or government—think that way. Sociopaths rise to the top—they’re not out-and-out psychopaths, so it’s not like they run around killing people and such, but they’ve accepted and internalized the system’s logic.

Whenever I hear this kind of question, I go back to the example of Big Tobacco. The companies hid the research about cancer from the public, but another fact is that the executives wanted to advance their careers and so the executives themselves—knowing about the research about cancer—chose to smoke and chose to allow and encourage their own children to smoke.

They used to have this line: “You are what you eat.” But the right line is: “You are how you make your money to eat.” How you make your money starts to define your consciousness, and the odd person understands and quits and breaks away, but on the whole it’s very hard for people to break out of the inertia of habit unless an external event really shakes them.

I can’t say that nothing’s changed on the climate, since a lot of people understand now who didn’t understand even five years ago, but people who have any kind of platform at all have to really focus on effective climate action as opposed to empty rhetoric.

I hope that people organizing in the trenches—whether it’s about unions or police injustice or crimes against Indigenous people—take up the climate question.

9) What do mega-elites like Larry Fink think that the world will look like in 2060 or 2070 or 2080? I don’t understand elite psychology—it would be beyond depressing to live in a fancy bunker in New Zealand if the world is burning down around you.

I don’t think elites care too much about that—what do rich people want to do? What’s the meaning of life for rich people right now? Get even richer, fuck, take drugs, spend money, buy stuff.

The Saudis are building a futuristic city for the super-rich, and rich people might be able to build fortresses all over the world, so you could have a dystopia with little paradises that are the equivalent of feudal castles, and we shouldn’t underestimate the degree to which there’s serious thinking and planning for a world like that. So the elites aren’t imagining bunkers, but instead beautiful protected cities, even if that’s an insane fantasy because millions of ordinary people won’t just lie down and let that fantasy happen.

Sections of the elite in their heart of hearts find most of humanity expendable and don’t care whether millions of people die off—right now how many children starve in the poorer countries, and how many elites give a shit?

Just look at child labor in the 1800s in England—I visited a mine in Wales where women and children had to work to avoid starvation, and the workers were essentially tortured and weren’t even allowed to urinate, and the women’s bodies becomes so twisted and their pelvises so weakened that they couldn’t have babies. And so it got to the point where the working class couldn’t even reproduce itself, but the mine owners didn’t give a shit because there were enough desperate unemployed people around that you could keep going.

But some elites realized that you eventually wouldn’t have a working class anymore if you allowed child labor and such terrible working conditions for women, so these elites joined forced with the rising and organizing working class—that convergence of interests led to laws that outlawed child labor and improved working conditions for women.

Will we see something like that now where sections of the elites will see that the status quo isn’t sustainable? That’s the big question. And so far, there’s a glimmer of elite concern, but it’s nothing substantial.

The preponderance of elites have a deep faith that capitalism will work it out in the end, that it’s only a matter of time before technological solutions like carbon capture will save them, and that—if worse comes to worst—they have the money to be OK until the technological solution arrives. Other than this deep faith, I can’t imagine what’s going through their heads, and maybe this deep faith is correct.

How do we reach ordinary workers with the message, though? That’s the challenge.

10) I didn’t mean to dwell on elites—it’s not necessarily productive to dwell on what goes on in Larry Fink’s mind or whatever, but obviously it’s a curiosity.

I don’t think it’s a frivolous topic—I think it’s a serious topic because as much as we have to find out how to talk to workers we actually do have to figure out how to talk to the elites and see if the elites can be divided between those who are really fascistic and those who would like to think that they’re liberal, who would like to think that they care about the world, and who do look at themselves in the mirror and worry about their kids.

Elites aren’t all sociopaths, and so we need to have these conversations, and I think that it’s far from a curiosity and is instead a very important topic. And in fact, I want to make this series with Ellsberg in part to shake elites out of their inertia and lethargy, since there’s no building a protected city when it comes to nuclear war—when nuclear war happens, it doesn’t matter how much money you have.

11) I read an article in the Financial Post that said that Canada will actually benefit from climate change. But we live in a highly interconnected global society, so if India and other places go down the tubes then how do you expect to insulate Canada from the repercussions? The Syrian Civil War was nothing compared to what lies ahead, and yet that conflict had massive repercussions all over the world.

And it’s not even true that Canada’s own climate will be OK—I mentioned to the climate scientist I interviewed that people are joking about growing mangoes in Muskoka, and he said that it’ll indeed be warm, but he said that there will be massive droughts in large sections of Canada and that the growing season will start and end earlier and earlier. When there’s less and less snow, where will your water come from?

So Canada might not get hit as terribly or as soon as the Southwestern United States, but it won’t be long before our water situation gets serious even in Canada. And you’ll have a dust bowl in Western Canada, and it’ll be terrible, and you’ll see more and more fires in British Columbia. And extreme weather events will hit Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes. So they’ve looked at it, and the Canadian situation gets very serious.

So I agree with you that it’s ridiculous to think that most of the world can be unlivable and somehow Canada can ignore that and just be OK, but even Canada will be in terrible shape.

Hope

1) What gives you hope in these cataclysmic times?

I’m interviewing a very successful organizer named Jane McAlevey who’s been a union organizer for a long time and who’s now training literally 1000s of organizers—my Reality Asserts Itself with her goes into her life and what she’s learned about organizing working-class people.

It’s exciting to interview her because she’s organizing and training so many organizers. My interview with her is all about real organizing—she gets workers to join unions and community organizations and political organizations, and she organizes people to make a difference in their workplaces and in their communities and in the electoral system.

She’s been very focused on winning, and preparing workers to win strikes, and getting people involved in elections. She calls it “whole worker organizing”—you organize everywhere in the community, including where people go to church and where people play sports.

She makes the crucial distinction between advocacy and organizing. Much of the left does advocacy where you have an issue and you make a lot of noise about it and you get people to sign up for it and you get people to vote in an election, but that work doesn’t bring people into any form of organization that has any force.

I think the left—including myself—needs to focus on organizing. What we can do in the media is so limited—it’s so easy to marginalize progressive organizations that rely on advocacy as opposed to organizing. We don’t want to rely on the fight for public opinion because the elites control mass communication and control the mass creation of public opinion, but the elites can’t control on-the-ground organizing. And you’ve seen organizing breakthroughs, including the progressives AOC has helped get elected in Queens and the Bronx and including progressives who’ve gotten elected to the New York State Assembly and who’ve gotten elected in other parts of the US.

So the only way out of all of this mess is a massive amount of organizing. And given how little time humanity has, some section of the elite will have to wake up soon too or else we’re toast.

2) What excites you about today’s political action?

I do find exciting the way that progressive types are getting elected at different levels in the US—less so in Canada—and the internet organizing apparently plays a secondary role in these campaigns where it’s real local organizing and they knock door-to-door, even though the internet played a very big role in the Sanders campaign in the US. And these electoral campaigns also become organizing campaigns, so there’s some hope there.

History’s weird, and sometimes there are galvanizing events and people suddenly break out of their inertia and their habits. In the lead-up to the Iraq War, millions of people around the world demonstrated against the war, and it wasn’t successful but that moment was really something—the most interesting thing about those protests was the number of people that had never been in a protest before in their lives and who suddenly just broke through.

Every so often, an objective event will shred American—or Canadian—mythology, and then people start to see the real world. When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, it was such a disaster, and suddenly the media discovered that there were such things as race and class in America, and they even talked about those issues for about three weeks. So there might be another galvanizing moment, and I just hope that progressive forces will build on that moment when it comes.

I lived in Baltimore for eight years, and there was that kind of moment when the police killed Freddie Gray, and 1000s of people came into the streets to protest the murder. I don’t think that I’d ever seen such broad support for police reform and such broad opposition to police abuse and so on. But there was no organizing, and it all dissipated.

So we’ll see if a moment like that comes—will we be able to take advantage of it?

That’s where we’re at.

3) We’ve covered extremely urgent topics and extremely serious topics, and it all sounds a bit apocalyptic, but to end on a hopeful note: What gives you hope in the face of these crises?

People organizing—direct organizing. There’s a shift of consciousness on climate, and you can see that far more people understand the danger than before.

But we’re reaching a real crossroads on climate. And in terms of China, the rhetoric and rivalry is very dangerous. So what gives me hope? Not a lot, to be totally honest.

But I’m with Ellsberg: You’ve got to act as if there’s still time to turn away from the iceberg.

I just hope that enough people will understand the urgency of the moment.