Is This the BIGGEST Thing?

My quick thoughts on self-regulation.

The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity. (One is unable to notice something because it is always before one’s eyes.)

—Wittgenstein

Many topics in our society deserve screaming headlines but are completely—or almost completely—undiscussed. One such topic is self-regulation. I have a whole series of pieces in the works on this topic—I plan to interview scientists and patients about this so that I can really get to the bottom of the topic.

But maybe I’m wrong. Maybe this topic does get attention and I’m just oblivious to the attention that this topic gets—let me know in the comments if you think that the spotlight on this topic is a lot brighter than I think.

Here’s a picture of what I’m talking about when I refer to “self-regulation”—take this with a grain of salt because I haven’t looked into the science on this matter yet:

There are a number of wild things about this topic—let me quickly bring up three points that jump out at me.

The Profound Centrality

First, self-regulation obviously must govern a person’s ability to succeed in life in every important respect. This seems completely tautological—how could it be otherwise? If you obliterate self-regulation, it follows that you’ll obliterate the following domains of humans life:

ability to succeed socially

ability to succeed romantically

ability to succeed in school

ability to succeed in a career

ability to complete complicated projects—not just planning a wedding, but virtually any major thing in life

ability to build structures and routines and habits that will make your life healthy and productive

ability to avoid the unhealthy habits that kill people, that burden health systems, and that cost governments billions of dollars

ability to be considerate and empathetic and compassionate toward other people

And conversely, those who succeed most in life presumably have exceptionally good self-regulation. But strangely, self-regulation isn’t a big thing that we talk about in our society—it’s true that we talk about people who “have their act together”, so maybe we talk about self-regulation in an indirect way.

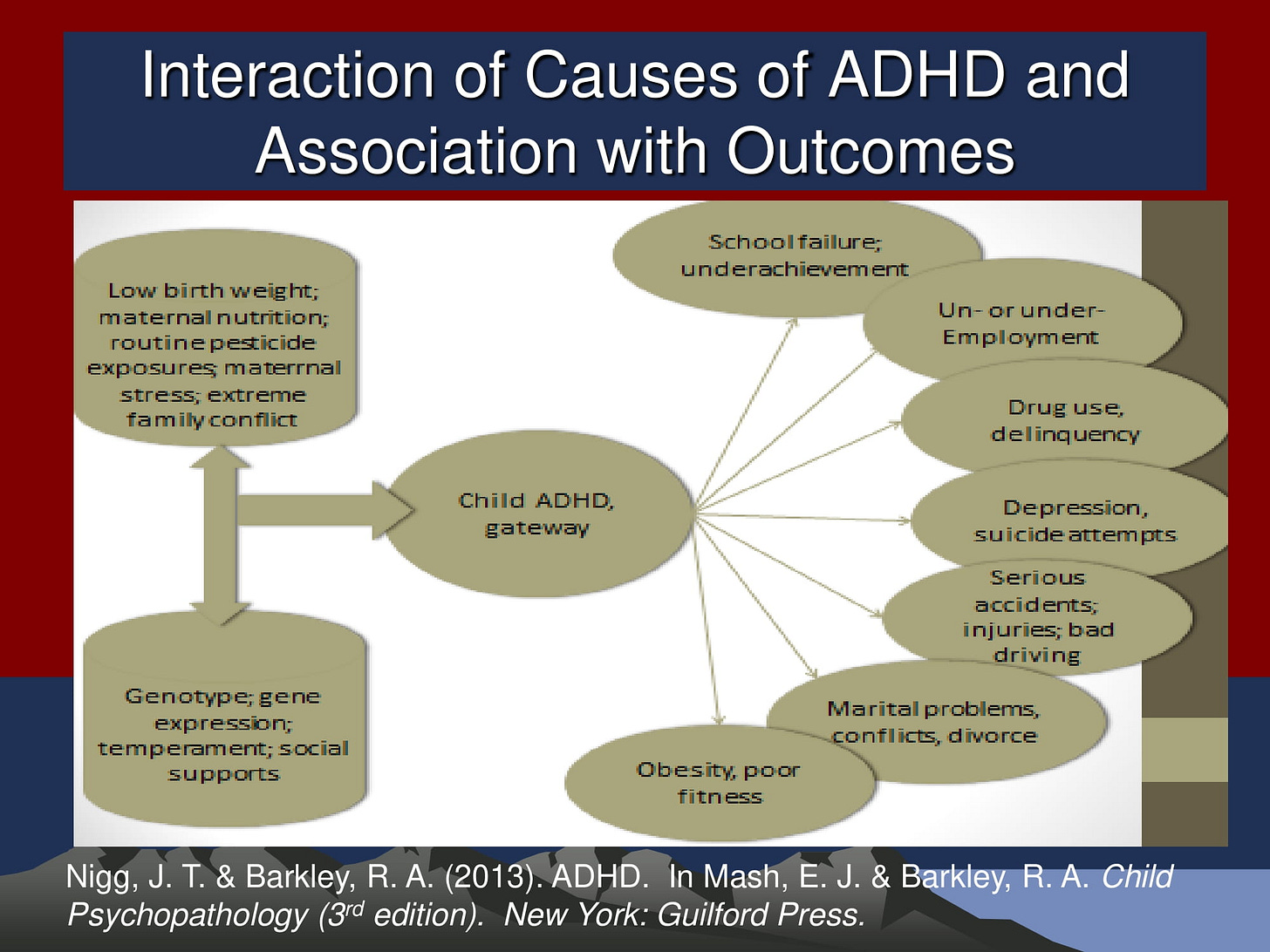

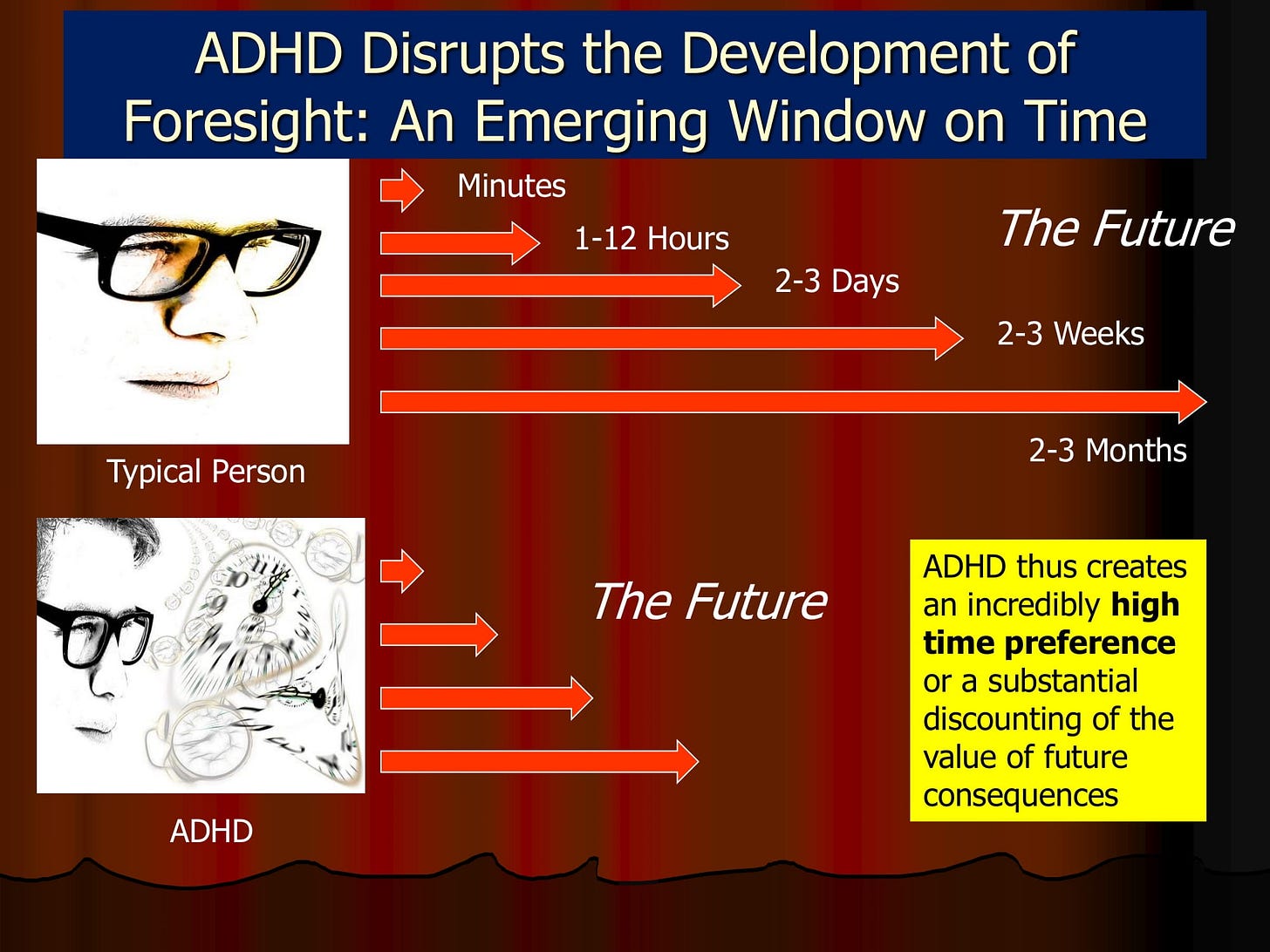

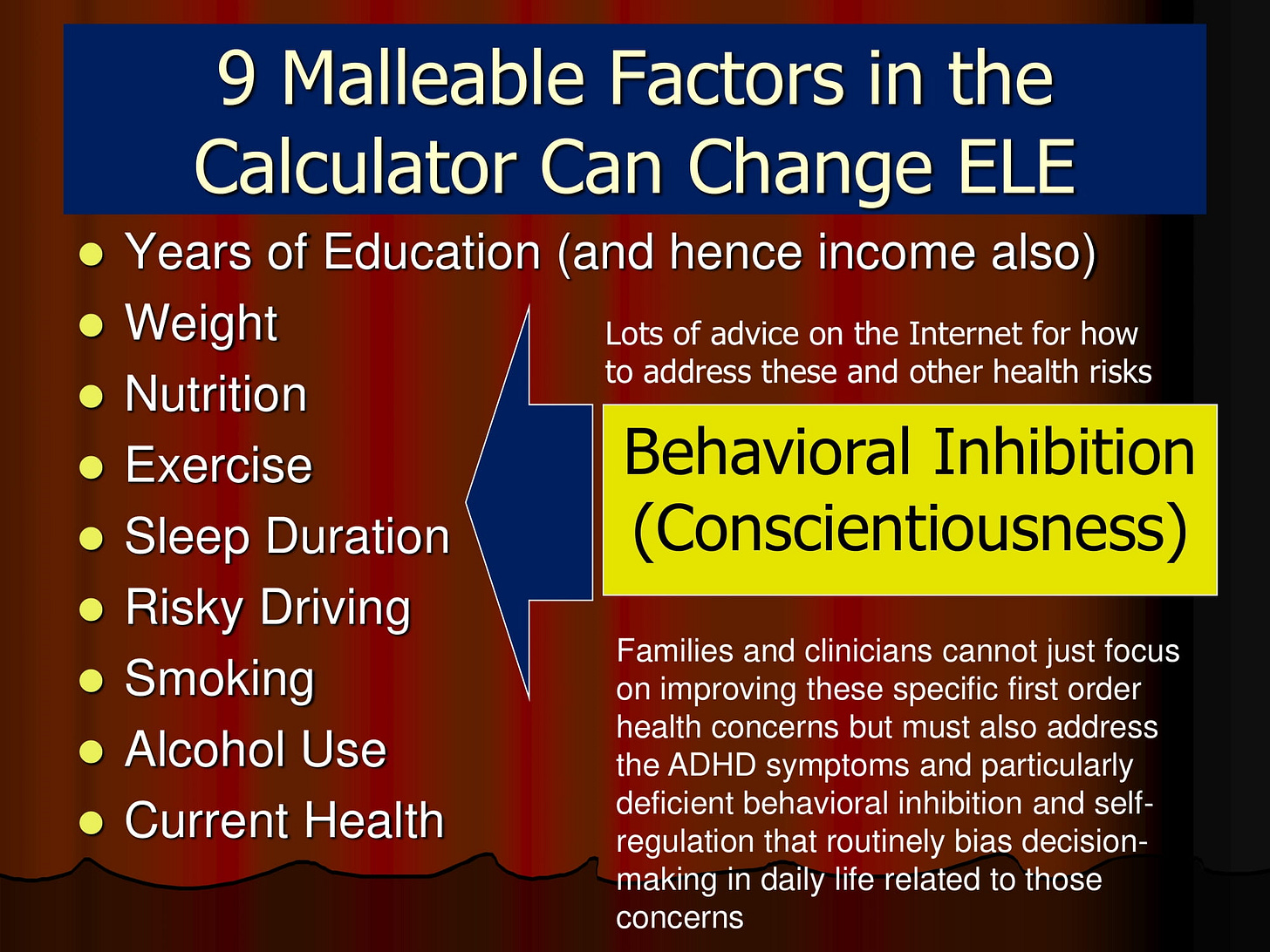

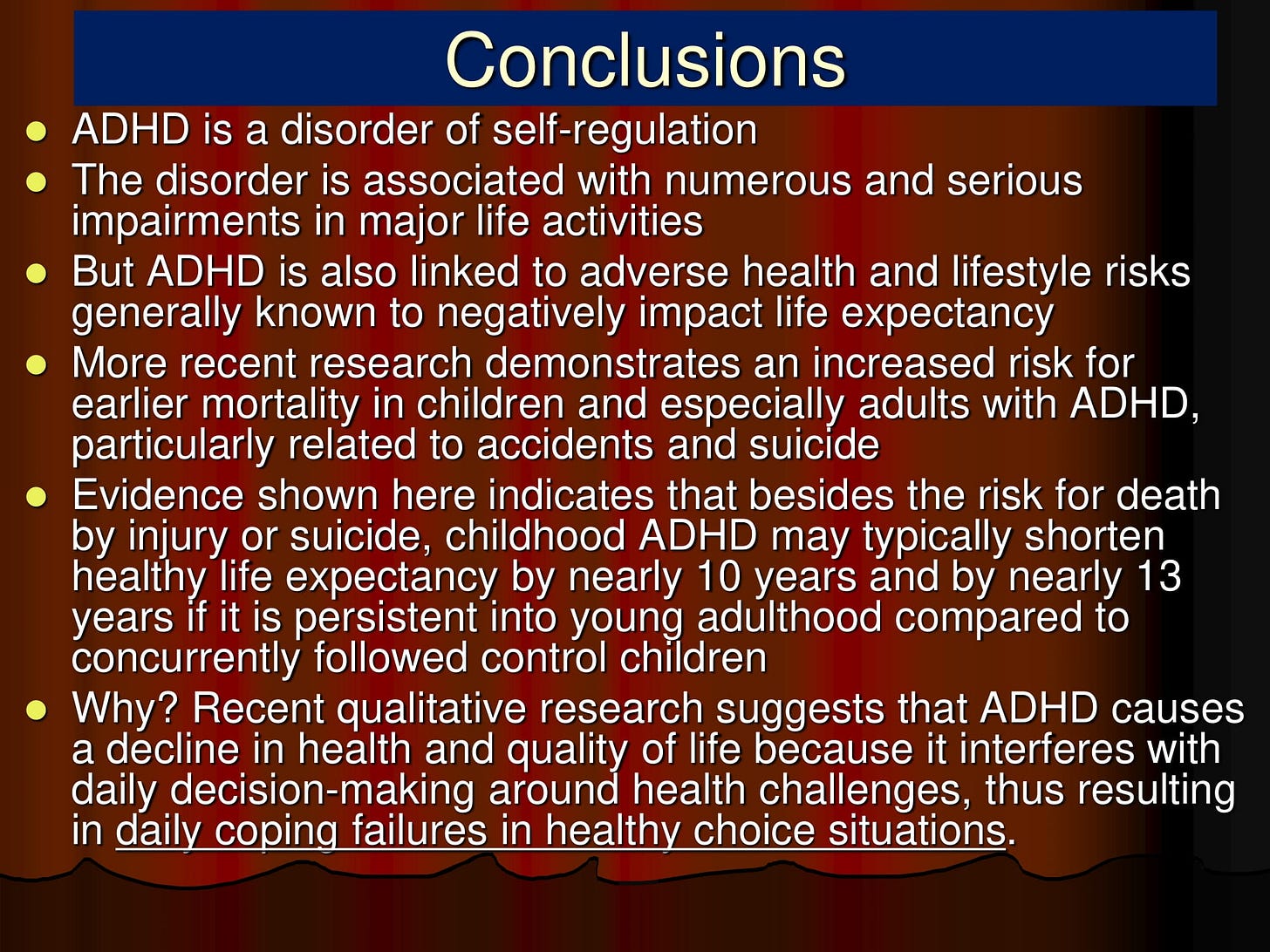

This slideshow gives a sense of self-regulation’s social and political consequences:

And this slideshow also gives a sense of self-regulation’s social and political consequences:

Make sure to take the two above slideshows with a grain of salt, since I haven’t looked into the science of this yet.

But take a look at the following slides from the above slideshows and think about what’s at stake socially and politically (note that the acronym “ELE” refers to “estimated life expectancy”):

Control and Responsibility

Second, it seems like awareness about self-regulation changes the way that you view humanity intellectually. If you’re aware of self-regulation, you’ll still feel anger and disgust at the things that other people think and say and do, but you’ll also recognize at an intellectual level that people aren’t necessarily in control and aren’t necessarily the authors of what they think and say and do—what are we to make of someone who’s a “lazy asshole” and then they pop a pill and 20 minutes later they’re productive and considerate and compassionate?

Just look at this video and tell me how control and responsibility fit into this picture—I haven’t vetted the science on this yet, so take it with a grain of salt:

Strangely Hidden Stories

Third, people who have clinically poor self-regulation apparently in at least some cases experience major improvement when they take certain medications, so where are these people and how can I interview them? To me, these people who respond to self-regulation medications in a dramatic fashion should be famous—their stories should be well-known and there should be incredible Hollywood movies about these people. I’m currently in the process of interviewing one of these people—I don’t know how many such people exist out there.

And it’s downright strange that I have to seek out these people—don’t the business interests that hold patents on the relevant medications have every financial incentive in the world to spotlight these people?

Back in November 2018, I was ramping up the dosage of a self-regulation medication that I was trying. I didn’t experience any positive effects until we reached a fateful threshold—at that threshold, I experienced what I call my “Miracle Week”, which was presumably a taste of treatment effect.

How can I even talk about the Miracle Week?

It seems impossible to talk about except through metaphor. And that’s one of the intriguing things about mental health—there’s a profound communicative rift and there are millions of people who would just frown at you with puzzlement or concern or both if you tried to articulate your experiences to them. Maybe people can only communicate things about mental health through art and metaphor—I’d love to write a film about self-regulation, and the film would rely heavily on metaphor to try to get across to the outsiders what self-regulatory impairment actually means.

A metaphor comes to my mind from Oliver Sacks’s incredible 2006 piece “Stereo Sue” about a stereoblind woman who acquired stereopsis:

Whatever its neurological basis, the augmentation of Sue’s visual world has effectively granted her an added sense, a circumstance that the rest of us can scarcely imagine. For her, stereopsis continues to have a quality of revelation.

“After almost three years,” she wrote, “my new vision continues to surprise and delight me. One winter day, I was racing from the classroom to the deli for a quick lunch. After taking only a few steps from the classroom building, I stopped short. The snow was falling lazily around me in large, wet flakes. I could see the space between each flake, and all the flakes together produced a beautiful three-dimensional dance. In the past, the snow would have appeared to fall in a flat sheet in one plane slightly in front of me. I would have felt like I was looking in on the snowfall. But now, I felt myself within the snowfall, among the snowflakes. Lunch forgotten, I watched the snow fall for several minutes, and, as I watched, I was overcome with a deep sense of joy. A snowfall can be quite beautiful—especially when you see it for the first time.”

And I also like Sacks’s piece “The Disembodied Lady” about a woman who lost her sense of proprioception—here’s an interesting paragraph from the piece:

She continues to feel, with the continuing loss of proprioception, that her body is dead, not-real, not-hers—she cannot appropriate it to herself. She can find no words for this state, and can only use analogies derived from other senses: ‘I feel my body is blind and deaf to itself…it has no sense of itself’—these are her own words. She has no words, no direct words, to describe this bereftness, this sensory darkness (or silence) akin to blindness or deafness. She has no words, and we lack words too. And society lacks words, and sympathy, for such states. The blind, at least, are treated with solicitude—we can imagine their state, and we treat them accordingly. But when Christina, painfully, clumsily, mounts a bus, she receives nothing but uncomprehending and angry snarls: ‘What’s wrong with you, lady? Are you blind—or blind-drunk?’ What can she answer—‘I have no proprioception’? The lack of social support and sympathy is an additional trial: disabled, but with the nature of her disability not clear—she is not, after all, manifestly blind or paralysed, manifestly anything—she tends to be treated as a phoney or a fool. This is what happens to those with disorders of the hidden senses (it happens also to patients who have vestibular impairment, or who have been labyrinthectomised).

People with self-regulatory impairment can definitely empathize with Christina when it comes to the “uncomprehending and angry snarls”—people with self-regulatory impairment receive “uncomprehending and angry snarls” 24/7/365 from the people around them, since few people in our society have any concept of what self-regulation is or what it might mean for a person to have self-regulatory impairment.

There are also videos like this online of people seeing color for the first time:

And I’d imagine that someone who experienced a permanent dramatic improvement in their self-regulation—how often does this ever actually happen, though?—might need therapy in order to come to terms with their pre-treatment life.

How would they look back on their pre-treatment life? When I imagine what it would be like to look back on one’s pre-treatment life from the vantage of effective medication, I think of the emotional scene in the 2015 film Room where the kid returns to a place and has a new vantage on the place and can’t believe that the place is actually the same place where he grew up.

Unfortunately, my Miracle Week only lasted a week. And scientists have no idea why medications stop working—I plan to interview a researcher about why medications stop working and find out what the various hypotheses are. I’m curious what percentage of psychiatric patients have had a medication work and then stop working—if the percentage is large, then making medications work permanently would absolutely revolutionize psychiatry, since all of those psychiatric patients would gain permanently whatever temporary benefit they’d experienced and then lost.

So how would I describe my Miracle Week, apart from the various metaphors? Here are the key points—these notes are partly based on the notes that I took during the Miracle Week, and in every instance where quotation marks appear below (even regarding “RAM”) I’m quoting from the November 2018 notes:

“I don’t feel elevated—just sharp as a knife, calm, and focused”

I felt an extraordinary stillness that I’d never felt before

to use a computer analogy, I felt like I had so much “RAM”—I felt like I could handle so much more in my mind and accommodate so much more in my mind

things that had been monumental, mountainous, impossible tasks were suddenly absolutely effortless—I effortlessly organized my whole apartment and effortlessly eliminated the clutter that had accumulated throughout my apartment

it was absolutely shocking how tasks at my minimum-wage job that used to seem incredibly difficult were suddenly so easy and so simple and so effortless—I immediately went from being the worst employee imaginable to being someone who found the job to be a complete breeze

my productivity and organization were way up—at one point, I noted that I’d gotten done in a single Miracle Week day what would’ve taken me a full week as my former self

I could read books; this ability to read was miraculous; I started to study math and planned to go back to university

I felt “in control”

my ability to suppress impulses was way up; whenever I felt an impulse to procrastinate or distract myself or say something stupid or whatever else, my brain had the ability to cut off that impulse and nip that impulse in the bud; I didn’t need to check on some little thing that I’d jotted down to make sure that it was perfect, but instead I was able to stifle the impulse and redirect my brain and move on

my brain would readily cooperate with me and would say: “OK, it’s time to work…I need to do this now and not be distracted with this random thing…it’s time to do important task X/Y/Z!”

during one shift at my job, I remember a wonderful miracle in which I visualized in my mind like a movie (1) the tasks that I’d already done during that shift and (2) the various task sequences that I might perform during the shift’s remainder

in contrast to my previous self, I got along well with my coworkers and wasn’t an asshole to them and didn’t blurt out every offensive and obnoxious thing that entered into my mind

in contrast to my previous self, I was much more considerate and empathetic and compassionate toward the people around me

And in addition to the above points, I also concurred with these five things that the medication—if successful—was supposed to do (this text is from my notes):

1. My thinking is sharper and it is qualitatively different than just an increase in focus and concentration.

2. I am more composed. I feel more in control of my decision-making.

3. I am more productive. I am getting more accomplished.

4. I feel that I am getting my act together. I am more organized and effective in what I am doing.

5. I get along better with the people around me at work and at school. I am smoother in my interactions.

During the Miracle Week, my aphantasia also somewhat went away—this was absolutely incredible for me, and I still think back with awe and wonder and delight on those moving and profound and jaw-dropping moments when I was able to see things in my mind and even rotate things in my mind.

I saw a shiny quarter in my mind—I could see the actual light actually glint off the quarter.

I visualized my parents’ faces and felt an emotional reaction and felt warmth. And I visualized my dog’s face—I smiled with delight. And I could look at the scene in front of me, and close my eyes, and actually hold in my mind an image of the no-longer-visible scene.

On visualization, here are some quotes from my Miracle Week notes:

“I can decently visualize and rotate people’s faces in my mind.”

“My ability to visualize is so powerful that it feels almost miraculous.”

“It gives me a smile to picture my mom’s face or my dad’s face or my dog.”

But I’m not sure what relation mental visualization has to self-regulation—there might be no relation at all for all I know.

I hope to get back the Miracle Week effects one day—someone told me this about the idea of going back on the medication that produced the Miracle Week:

I don’t see the harm in your trying for your Miracle Week again and seeing if it might last longer. We are quite ignorant about the brain’s compensatory mechanisms, and it is possible that it will be better this time.

For now, my Miracle Week remains a source of profound and moving and piloerective inspiration for me that gets me out of bed in the morning and gives me a jolt of inspiration whenever I feel bad.

I think back with awe on the shiny quarter and the way that the light glinted off it—that quarter existed inside of me and inside my mental theater and symbolizes to me the Miracle Week and all of the awe-inspiring experiences that the Miracle Week contained.

I’m excited to interview scientists and patients about self-regulation—self-regulation is a major topic that seems to me to deserve a lot more attention than it’s gotten.

Self-regulation can only be effective when you know the “correct” behaviors for situations. How do you learn those “correct” behaviors, if no one teaches you?

My sister and I grew up half wild in a poor community — parents were busy eking out a living. They were good people, but immigrants who had no relatives here and didn't know many American customs. So we learned the basic morals, but not basic social behaviors — the lack of which result in other people laughing or talking about you behind your back, or disliking you, or exploiting your naïveté. There are many children born into poverty with those problems. And it’s teachers who end up having to deal with them — and they only have time for the very basics.

Neurologists and psychiatrists and many psychologists won’t tell you what behaviors are acceptable or unacceptable in society or at work. No matter how much self-regulation you have, it will not teach you the social behaviors to which your self-regulation is aimed at your adhering.