The GOP used to be much more ideologically diverse. Noam Chomsky used to visit the home of a Republican congressperson Chomsky knew—that’s unthinkable today.

Chomsky wrote in 2016:

Both parties have moved to the right during the neoliberal period of the past generation. Mainstream Democrats are now pretty much what used to be called “moderate Republicans.” Meanwhile, the Republican Party has largely drifted off the spectrum, becoming what respected conservative political analysts Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein call a “radical insurgency” that has virtually abandoned normal parliamentary politics. With the rightward drift, the Republican Party’s dedication to wealth and privilege has become so extreme that its actual policies could not attract voters, so it has had to seek a new popular base, mobilized on other grounds: evangelical Christians who await the Second Coming, nativists who fear that “they” are taking our country away from us, unreconstructed racists, people with real grievances who gravely mistake their causes, and others like them who are easy prey to demagogues and can readily become a radical insurgency.

Chomsky was referring to these comments from respected conservatives Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein:

The framers designed a constitutional system in which the government would play a vigorous role in securing the liberty and well-being of a large and diverse population. They built a political system around a number of key elements, including debate and deliberation, divided powers competing with one another, regular order in the legislative process, and avenues to limit and punish corruption. America in recent years has struggled to adhere to each of these principles, leading to a crisis of governability and legitimacy. The roots of this problem are twofold. The first is a serious mismatch between our political parties, which have become as polarized and vehemently adversarial as parliamentary parties, and a separation-of-powers governing system that makes it extremely difficult for majorities to act. The second is the asymmetric character of the polarization. The Republican Party has become a radical insurgency—ideologically extreme, scornful of facts and compromise, and dismissive of the legitimacy of its political opposition. Securing the common good in the face of these developments will require structural changes but also an informed and strategically focused citizenry.

Mann and Ornstein also wrote this:

The approach of the minority party for the first two years of the Obama administration was antithetical to the ethos of compromise to solve pressing national problems. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a plan which included $288 billion in tax relief, garnered not one vote from Republicans in the House. The Affordable Care Act, essentially a carbon copy of the Republican alternative to the Clinton administration’s health reform plan in 1994, was uniformly opposed by Republican partisans in both houses. A bipartisan plan to create a meaningful, congressionally mandated commission to deal with the nation’s debt problem, the Gregg/Conrad plan, was killed on a filibuster in the Senate; once President Obama endorsed the plan, seven original Republican co-sponsors, along with Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell, joined the filibuster to kill it. McConnell’s widely reported comment that his primary goal was to make Barack Obama a one-term president—a classic case of the permanent campaign trumping problem-solving—typified the political dynamic.

And this:

The best we can hope for is a more tempered Republican Party willing to do business (that is, deliberate, negotiate, and compromise without hostage-taking or brinksmanship) with their Democratic counterparts.

Gridlock harms and damages a country, and causes great destruction, and ruins people’s lives—it’s ethically shocking that a political party would strategically induce gridlock in order to roar back into power based on voters’ gridlock-induced anger.

But regardless of the ethics, Mitch McConnell seems to have an explicit agenda of political arson—as Chomsky commented:

The stimulus bill has its flaws, but considering the circumstances, it’s an impressive achievement. The circumstances are a highly disciplined opposition party dedicated to the principle announced years ago by its maximal leader, Mitch McConnell: If we are not in power, we must render the country ungovernable and block government legislative efforts, however beneficial they might be. Then the consequences can be blamed on the party in power, and we can take over. It worked well for Republicans in 2009—with plenty of help from Obama. By 2010, the Democrats lost Congress, and the way was cleared to the 2016 debacle.

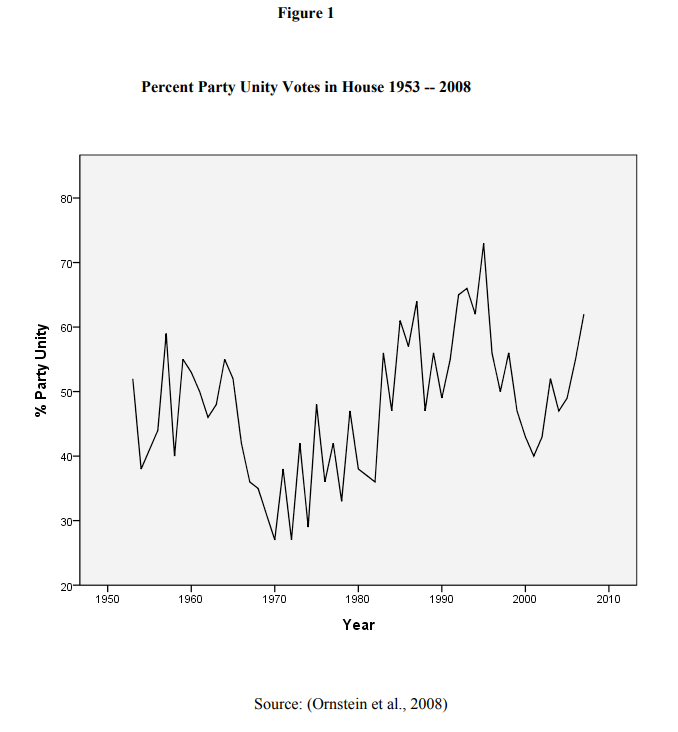

How did we get here, though? Thomas Ferguson’s fascinating 2011 paper “Legislators Never Bowl Alone” offers a fascinating answer: political money.

Political money drove both parties to the right—the Democrats became moderate Republicans and the Republicans went off the cliff. But political money also polarized Washington in remarkable ways.

Ferguson’s paper is extremely interesting to read, though “Table 3” needs to be corrected because it has a formatting error—here are Ferguson’s main points (I added hyperlinks):

“Gingrich, Republican National Chair Haley Barbour, and National Republican Senatorial Committee Chair Phil Gramm orchestrated a vast national campaign to recapture Congress for the Republicans in the 1994 elections”

“The House result was a true shocker: it marked the first time Republicans controlled that body since 1954”

“Gingrich and his leadership team, which included Dick Armey and Tom (‘the Hammer’) DeLay, institutionalized sweeping rules changes in the House and the Republican caucus that vastly increased the leadership’s influence over House legislation”

Gingrich and his team “implemented a formal ‘pay to play’ system that had both inside and outside components”

“DeLay and other GOP leaders, including Grover Norquist, who headed Americans for Tax Reform, mounted a vast campaign (the so-called ‘K Street Project’) to defund the Democrats directly by pressuring businesses to cut off donations and avoid retaining Democrats as lobbyists”

“Inside the House, Gingrich made fundraising for the party a requirement for choice committee assignments”

“The implications of auctioning off key positions within Congress mostly escaped attention, as did the subsequent evolution of the system into one of what amounted to posted prices”

“Democrats rapidly emulated the formal ‘pay to play’ system for House committee assignments”

there was a “sharp rise in campaign contributions from members of Congress of both parties to their colleagues and the national fundraising committees”

“Soon leaders of the Democrats, too, were posting prices for plum committee assignments and chairmanships”

like the GOP had done, the Democrats “centralized power in the leadership, which had wide discretion in how it treated bills and more leverage over individual members”

“not only new members, but older Senators and members of the House with previously moderate records joined the headlong rush to extremes”

“In both the Senate and the House, leaders increasingly resorted to complex parliamentary procedures to make life difficult for the other party and sometimes minority factions within their own”

So Newt Gingrich and those around him changed the game, and the new game yielded sharp polarization in the both the Senate and the House.

And the media played an interesting role in the sharp polarization:

“the mass media appear to have polarized right along with Congress”

“Pushed by private broadcasters, the Reagan administration extensively deregulated broadcasting”

“networks, led by Rupert Murdoch’s Fox News (headed by Roger Ailes, a former Nixon campaign consultant) increasingly abandoned even the appearance of objective reporting, in favor of evident partiality toward one or the other major party, but especially toward conservatives and the center-right members of both parties”

“The proportions of ‘buzzwords’ used in news stories—that is, the ‘slant’ of the news—closely tracks the mix used in Congressional debates and speeches”

“The feedback loop running from Congress to the mass media and back again amplified the process of polarization”

“Congressional leaders of both parties now focused intently on creating sharper party profiles (‘brands’) that would mobilize potential outside supporters and contributors”

these leaders “spent enormous amounts of time and money honing messages that were clear and simple enough to attract attention as they ricocheted out through the media to the public”

these leaders “staged more and more votes not to move legislation, but to score points with some segment of the public or signal important outside constituencies”

these leaders “made exemplary efforts to hold up bills by prolonging debate or, in the Senate, putting presidential nominations on hold”

these leaders “set formal or informal quotas for congressmen and women—here even conservative Republicans stoutly defended equal rights—for member contributions to the national congressional committees”

“national fundraising committees, in turn, poured resources into elections to secure and hold majority control”

what took shape was “centralized parties, presided over by leaders with far more power than in recent decades, running the equivalent of hog calls for resources, trying to secure the widest possible audiences for their slogans and projecting their claims through a mass media that was more than happy to play along with right thinking spokespersons of both parties”

“members, in turn, scrambled to raise enough money to meet the quotas the leaders set as the price of securing influence in the House or the Senate”

According to Ferguson, what I’ve just laid out—and not any shift in public opinion—is the actual explanation for polarization. So to undo polarization, I guess that we have to undo the changes that Gingrich and his allies made and put the genie back in the bottle.

In my view, Ferguson’s paper deserves far more attention that it’s received.

Money is a big deal—you should always look at political money when you want to try to understand something like polarization. I don’t know what percentage of a congressperson’s time is spent reading and crafting legislation as opposed to raising money, but I’d like to find that out—Ferguson’s paper includes the following interesting quote:

Under the new rules for the 2008 election cycle, the DCCC [Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee] asked rank and file members to contribute $125,000 in dues and to raise an additional $75,000 for the party. Subcommittee chairpersons must contribute $150,000 in dues and raise an additional $100,000. Members who sit on the most powerful committees…must contribute $200,000 and raise an additional $250,000. Subcommittee chairs on power committees and committee chairs of non-power committees must contribute $250,000 and raise $250,000. The five chairs of the power committees must contribute $500,000 and raise an additional $1 million. House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, Majority Whip James Clyburn, and Democratic Caucus Chair Rahm Emmanuel must contribute $800,000 and raise $2.5 million. The four Democrats who serve as part of the extended leadership must contribute $450,000 and raise $500,000, and the nine Chief Deputy Whips must contribute $300,000 and raise $500,000. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi must contribute a staggering $800,000 and raise an additional $25 million.

And see these interesting figures from Ferguson’s paper: